Infrastructural Interactions

Contents

Infrastructural Interactions

Methods (or not) for Infrastructural Interactions

- Peripheral politics (workshop with Helen V Pritchard and Femke Snelting)

- The politics of listening (workshop with Miriyam Aouragh and Seda Gürses)

- word2complex (workshop with Varia)

- Infrables (workshop with Varia and titipi)

- Other Weapons, What have you given up in the name of safety? (research report)

- Clareese Hill, Impossible Breathing Modular Meditation Praxis

- Gwen Barnard, Naomi Alizah Cohen, Notes Towards an Antifascist Infrastructural Analysis (research report)

- Yasmine Boudiaf, Listening Structures

- Bugreporting as a method

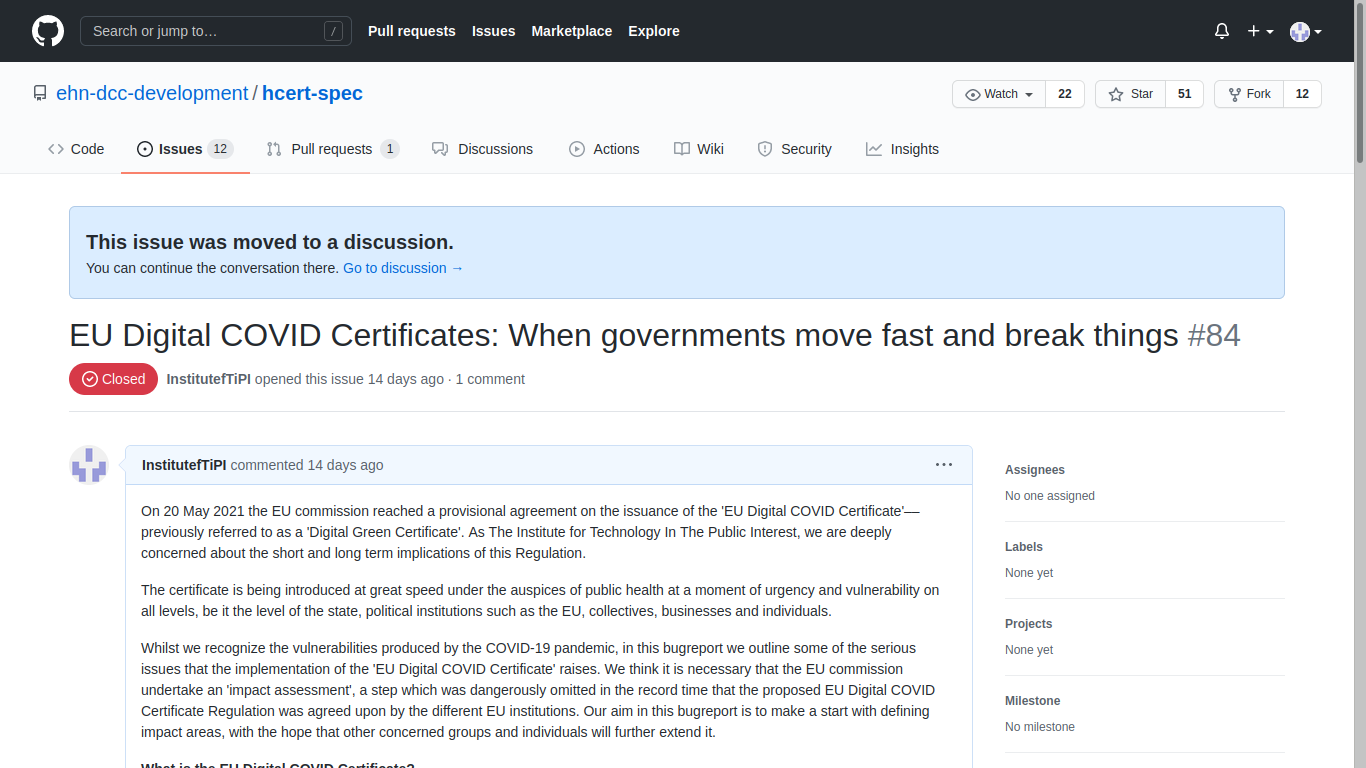

- When governments move fast and break things (bugreport)

Appendix

- Infrastructural Manouevres, wiki-to-pdf (how this publication was made)

- Contributors

- Colophon

Infrastructural Interactions: Survival, Resistance and Radical Care

Cristina: Even if the infrastructure fails, there's all this imagery around it that connects to progress, ideas of progress, and ideas of modernity and that has a lot of rhetorical power. I think thinking about other ways politics or other ways of interacting with, of building an image around infrastructures is really valuable, actually. At least, for me, the most convincing that I've encountered, I don't know.

Clareese: Definitely, yes. I do agree too. Infrastructure or the idea that it's not going away, so how do you use it and make it useful to the people that it's supposed to act as a container or a boundary around?

Radical Care

As public health care nearly collapsed under pandemic pressure, schools closed and movement through public life became increasingly monitored and managed by digital infrastructures, we have been thinking with other collectives about radical alternatives to the need for care. For the last two decades, basic care provisions have been turned into tools that perform racial capitalism, excluding and punishing those who needed it most. What kind of solidarity and support can people extend and receive to one another that is outside the scope of the limits that are being imposed on us, from the voluntary duty of care to not expose one another, to a state supported obligation to function as a subject to capitalism? The fact that the pandemic made it impossible to come together physically to organise and to resist, triggered many discussions and reflections. When lockdowns immobilised a lot of the practical options that common people and ordinary working-class people have for resistance, which would be their bodies and the street, or meeting to make plans or to provide care for each other, cloud infrastructure has often been presented as the way forward — such as hosting organising over Zoom, using Google Drive to distribute materials or Uber to distribute care packages.

For the conversations and workshops that feature in this manual, we brought together people involved in alternative healthcare or other alternative care-structures, for example in the context of anti-fascist activism, or groups rethinking alternative technical infrastructures in terms of capacity and care. Without wanting to turn everything into infrastructure, we felt it was helpful to open up perspectives that point out the worlding qualities of caretaking, maintenance and instituting.

From survival to resistance in racial capitalism

As people who are active on the ground, but also intellectually, what do we imagine in terms of resisting and building alternatives for or to cloud infrastructures? What are our lived experiences with infrastructures that demand these alternatives? A question that came up often in our discussions and practices was whether this is a time of survival, or a time of resistance? Are the creative imaginaries we are exchanging, an example of resistance ... or are they actually about just surviving? We were interested in asking this question, because we know that people are sometimes using extractive services and apps, knowing very well that it's a risk, and that by using them, they're actually being exploited even more.

In the workshops, conversations and collective writing that generated this workbook, we have tried to think resistance under racial capitalism and issues around extractivism with participants from different geographies and practices. What are the material aspects of cloud infrastructures that are being imposed on us, during COVID-19 lockdowns and since? It felt these questions where erased from the debate, even among critical scholars working on technology, while obviously racial capitalism and extractivism are part of the conversation. This workbook brings attention to the ways in which computational infrastructures extend extractivism, from the mining of rare minerals for smart phones to the extractivist models of cloud-based services and the extension of Big Tech into the markets of care. To do so, we build on a body of literature pointing out the continuing geopolitical make-up of imperial and colonial power in the development of infrastructural technologies. In particular, Syed Mustafa Ali argues for a decolonial approach when designing, building or theorizing about computing phenomena and an ethics that especially decentres Eurocentric universals.Ali, S. M. (2016), ‘A brief introduction to decolonial computing’, XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students, 22:4, pp. 6–21. Paula Chakravartty and Mara Mills offer to think decolonial computing through the lens of racial capitalism.Chakravartty, P. and Mills, M. (2018), ‘Virtual roundtable on decolonial computing’, Catalyst, 4:2, p. 14 Cedric Robinson argues that mainstream political economy studies of capitalism do not account for the racial character of capitalism or the evolution of capitalism to produce a modern world system dependent on slavery, violence, imperialism and genocide.Robinson, C. ([1983] 2000), Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press Capitalism is ‘racial’ in the very fabric of its system.Bhattacharyya, G. (2018), Rethinking Racial Capitalism: Questions of Reproduction and Survival, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

The work documented in this workbook is embedded in a view that requires continuous undoing – a necessary but unfinished formal dismantling of colonial structures by decolonial resistance. Building on theories of racial capitalism, we focus on the implications of computational infrastructures and their relation with extraction, whilst working on ways to develop a non-extractive research practice.

What does Cloud infrastructure do?

Cloud infrastructures purposefully promote data intensive services running on the infrastructures, rather than pre-packaged and locally run software instances. These data-infrastructures range from health databases, border informatics, data storage warehouses, to city-dashboards for monitoring citizen flows, educational platforms and the optimisation of logistics. It has become common for theorists, activists, artists, designers and engineers that want to critique cloud services, to focus on the way they extract data from individuals, either for value or surveillance, or to automate services so that institutions can reduce workers rights or employ less people. The research we are doing at TITiPi however evidences quite clearly that this might not be the best way to understand what clouds are and how to resist and prepare for the massive shifts in public life they are and plan to make.

Instead, we propose that what we need to look at how Big Tech cloud services are financialising literally everything on a rentable model, thereby indebting institutions, communities and individuals to their values and services. Cloud infrastructures offer agile computational infrastructure to administer, organise and make institutional operations possible, decreasing the potential for institutions to manage their own operations, locking them into a cycle of monthly payable subscription agreements (debts) and rendering all operations from emptying bins, to paying bills, to hosting collaborative documents ready to be financialised by Big Tech cloud companies. They do this by promising a future of being able to fullfill the operations that institutions themselves might not even have imagined. By interfacing between institutions and their constituents through Software-as-a-Service solutions, they reconfigure the mandate of institutions and narrow their modes of functioning to forms of logistics and optimization.

As Big Tech extends into public fields, they tie together services across domains, creating extensive computational infrastructures that reshape public institutions. So the question is, how can we attend to these shifts collectively in order to demand public data infrastructures that can act in the "public interest"? And how can we institute this? Computational infrastructures generate harms and damage beyond ethical issues of privacy, ownership and confidentiality. They displace agencies, funds and knowledge into apps and services and thereby slowly but surely contribute to the depletion of resources for public life. While data- infrastructures capture public data-streams, they also capture imagination for what a public is, and what is in its interest. We urgently need other imaginations for how we interface with infrastructures, beyond delivering a “solution” to a “need” (or the promise they can fulfill a future need).

The workshops, documentation and structures in this workbook are a small contribution to making this complex paradigm shift together.

Research as kinship

Cloud infrastructures are typically hard to study and we need imaginative and collective methods to trace the long tail of their effects and make them legible. In the work of TITiPI and in this workbook, creative practice and collective organising is vital to restructure both the way we research and how we understand infrastructural implications. In the conversations and workshops, we attended to our companions' proposals for socially and technically remaking or resisting infrastructures. These conversations and workshops attended carefully to the shapes that we make for research to happen within and we resisted (where we could) using extractive cloud infrastructure. Instead the conversations and workshops took place using a patchwork of otherwise-hosted Free, Open Source softwares. This publication for example was made with an implementation of wiki-to-pdf, allowing the workbook to be collaboratively edited and published without needing to use graphics cloud based software such as Adobe Creative Cloud. Within the institute we are committed to shaping research differently, and we have a sneaky feeling that the possibility of our imaginations of different institutes and infrastructures are interdependent on the infrastructures we use to communicate, write, make and do research. So many tools and infrastructures for research are extractive, damaging and harmful, how come we so often ignore this part of the relationality? As Femke once said: "these tools are so banal people can't even bear to think about how they are shaping their research." So we also try to practice radical care here, to attend to the infrastructures we use and their extractive forces.

In the research that led to this manual we combined creative practice, queer theory, historical materialism, critical computing, together with approaches from infrastructure studies to disclose the shifts and damages of cloud infrastructures. In a series of conversations, we documented stories and experiments of inventive ways to trace and disclose these effects.

One of our strong motivations was to connect people through the research conversations and workshops. We wanted to start the conversations by asking questions, but also inviting our collaborator's, companions and future instituters to intervene in each other's answers or to frame the discussion with each other. This is also how this workbook was written. The workbook itself was composed together with artists, technologists and activists, committed to non- extractivist research practices for and with refugees, anti-racist, trans* health and sex work, and our hope is that through the workbook you will also get to know these different groups and networks. To get to know the imaginative ideas, suggestions and experiences, if you will, of The Institute for Technology in the Public Interest, and for our companions.

The transcultural and differently situated conversations that fueled this research, inquired into and documented creative and grassroots approaches for counter cloud infrastructures that are being built, or will need to be built. They revealed the intricate ways in which power asymmetries by design necessitate us to shift our critical analysis from the received idea that the main problems with cloud infrastructures and digitalisation are centered around personal data, privacy and surveillance, to a much more complex perspective that takes the political economy and financialisation of institutions operations of cloud infrastructures into account. Here we share some of the crossings from these conversations which get taken up in different ways throughout this workbook.

Infrastructural imaginary

Anita: What is missing in school is a discourse on algorithms, and the politics of the technical; there is no grounding of this in the everyday. It is admitted that tech questions are important but there is no concrete way to engage with it, it is not part of life. The researches that are happening on technology are always treating it as a topic: The Bot, The AI ... it is not part of normal life with technology. The workshops we are organising are grounded in choices we are living in, technologies we are using every day ... this is where connections are made.

Naomi: I think when it comes to anti-fascist politics, it's not actually just the infrastructure of the street that you're working to remove from fascist organising.

Arun: The question is how do we keep fighting for the near future? Black Lives Matter is quite a broad open space as a physical concept. The physical concept is very broad. It can mean, the thing that Google puts out saying, we support Black Lives Matter, or it can mean Ruth Gilmore's idea of abolition and ending racial capitalism. It's a massive spectrum. The question is, how do we create organisational infrastructure to make sure it's the second of those and not the first? That seems to be the problem across the board in terms of radical politics.

Miriyam: Yes.

Seda: Now you know why we're called The Institute.

Arun: Yes.

Seda: Nothing more, nothing less.

Arun: Thank you. There you go. I set it out for you nicely, right?

From survival to resistance in racial capitalism

Arun: For certain communities, just defending your own sociability relationship is itself political. Just to keep either alive and survive is itself political because you have a community politics history that is already there. So in keeping the community alive, you keep that politics alive.

Miryam: Obviously, also a very important theme is resistance. What forms of resistance have people managed to design or come up with or discover? As they say, need is the mother of invention, the father of invention, the grandmother of invention.

Seda: The cousin.

Miryam: The cousin. Everything. It's through needs. Working-class people, it's through need that they come up with. It's not some blueprint thing that some very smart organisation told them to think about making and developing. It's resistance is one of the themes as well. I think these are roughly the themes that we had thought of.

Radical care

Nadia: Yes, radical care is a big question. In the group that I'm following of the families, I think for me the radical care is really in the WhatsApp group of the grandmothers who send each other. One of them sends the other mothers every morning a good morning and she says “bonjour les mamans” every morning and asks the mothers how they are doing. These are all people who haven't seen their children or grandchildren for more than eight years. Who don't know whether they will see them back, who have lost children and grandchildren also in many cases and the kind of daily hope basically of trying to keep hope alive.

Sometimes it comes up, sometimes it goes down, and then they started basic stuff like saying hi to each other every morning and then it's followed by hearts and emoticons and these kinds of things. Emoticons play a very important role in the WhatsApp group. I'm always impressed. It's very stupid but I'm always impressed by the tenacity of it.

Methods (or not) for Infrastructural Interactions

Peripheral politics

A workshop with Helen V. Pritchard and Femke Snelting

"As such, urban politics will largely be a peripheral politics, not only a politics at the periphery, but a politics whose practices must be divested of many of the assumptions that it derived from the primacy of 'the city'.”AbdouMaliq Simone, Improvised Lives (Polity Press, 2019)

During this on-line session, we worked with eight conversations on infrastructural shifts that TITiPI had organised with companions in the months before. To attending to the stories that were told and the surprising details that came up through the rhythm of three refrains, was an attempt to listen for the experiences of living with infrastructure but also for other worlds of radical care and different temporalities not defined by Big Tech infrastructure nor by academic methods, worlds that are already here, that are already being practiced.

In this workshop, we tried not to fall for the suggestion of a coding or analysis that might make sense of transcripts from the outside, we listened together to generate a poetic-theory of infrastructure. We generated an understanding that was feeling into the surges of life, or what AbdouMaliq Simone calls "the rhythms of endurance with infrastructure".Simone, Improvised Lives.

We borrowed the idea of 'refrain' from Kara Keeling who suggests that we need to be attentive to another world that is possible because it is already here.Kara Keeling, Queer Times, Black Futures (New York: New York University Press, 2019). Sensing the different organizations of things, different systems of signification and value, so much so that it might give way to the another world. Sung in the refrains with other temporalities and coordinates, yet already here."The generative proposition another world is possible, the insistence that such a world already is here now and it listens, with others, for the poetry, the refrains, the rhythms, and the noise such a world is making." (Keeling, Queer Times, Black Futures)

Perhaps this world gives way in the peripheries, AbdouMaliq Simone reminds us of the importance of what he calls a 'peripheral politics', of a-centric practices and rhythms: "[s]urges of rhythm emerges from attempts to reach beyond the confines of limited places and routines, and yet retains a microscopic view of the constantly surprising details about the places that could be left behind".Simone, Improvised Lives

The workshop 'Peripheral Politics' was a way to organise and categorise research material not based on the extraction of meaning but on the collective listening and responding-too through a set of interconnected prompts. The transcriptions opened up onto urgencies, repetitions of stories, giving ways to other worlds, partially told.

Peripheral listening

- Hold a series of open conversations with companions and associates on a subject matter that is felt as urgent, but which is not yet fully seen or comprehended.

- Transcribe the conversations or ask a companion to do so.

- Invite everyone that participated in the conversation for a two hour workshop.

- To keep a shared rhythm whilst reading, propose a set of three 'refrains' as things to hold while reading, listening and responding to the material. These 'refrains' can be quotes, phrases or aphorisms that intuitively resonate with the transcriptions.

- Publish each conversation on an on-line notepad such as etherpad, or print them out on paper in case you are all in the same room.

- Split up in small groups (two or three people) and chose one conversation. In case of an on-line workshop, also open a channel by which you can hear each other. Many on-line video-services have a breakout-room feature but this adds a layer of efficient management that might be blocking the exercise.

- Choose together one of the refrains to hold on to.

- One person reads the conversation out loud while the others use the chat function to simultaneously associate, rhyme and respond alongside the conversation. For IRL, use pen and paper.

- Experiment with selecting parts of the interviews through a collective process that resisted more extractivist ways of coding, sorting and labeling.

- Create a series of poetic openings and peripheral attention in the margins of the transcripts by listening to to the material in this indirect way.

- After 20-30 mins, take a short break and change roles at least once.

- If you've got time, regroup and refrain another conversation using the same method.

- Come back together and discuss.

Refrain to hold on to: beginnings that happen in the middle of things

a little song, a nocturnal creation myth or ‘sketch’ in the middle [...]; it is not a genesis story of the logos and light, but a song of germination in darkness [...] I begin with it because doing so calls attention to the improvisational elements of any beginning, which always happens in the middle of other things.

Kara Keeling, Queer Times, Black Futures

Refrain to hold on to: making the most of the hinge

Here, the surge as rhythm emerges from attempts to reach beyond the confines of limited places and routines, and yet retains a microscopic view of the constantly surprising details about the places that could be left behind. This is a rhythm of endurance, of surging forward and withdrawing. It is not a rhythm of endless becoming nor of staying put; it is making the most of the “hinge,” of knowing how to move and think through various angles while being fully aware of the constraints, the durability of those things that are “bad for us” (Stoler 2016).

AbdouMaliq Simone, Improvised Lives

Refrain to hold on to: start with the small things, while keeping in mind the big ones

Any "archipelagic" thought is a trembling thinking, it is about not-presuming, but also about opening and sharing. We do not need to define a Federations of States first, or to install administrative and institutional orders. It already begins its work of entanglement everywhere, without being concerned with establishing preconditions. As far as our relations in the Archipelago are concerned, let us start with the small things, while keeping in mind the big ones.' (Toute pensée archipélique est pensée du tremblement, de la non-présomption, mais aussi de l'ouverture et du partage. Elle n'exige pas qu'on définisse d'abord des Fédérations d'États, des ordres administratifs et institutionnels, elle commence partout son travail d'emmêlement, sans se mêler de poser des préalables. S'agissant de nos rapports dans l'Archipel, commençons par les petites choses, tout en ayant en l'esprit les grandes.)

Edouard Glissant, Traité du tout monde

Print out refrains: http://titipi.org/projects/infrastructuralinteractions/refrains.pdf

Transcript marginalia from the workshop

Refrain: "start with the small things, while keeping in mind the big ones"

- F: among the group is in your world

- F: everywhere ceasing the moment

- F: many chats i am in

- F: multiplicity access points

- F: distributing power

- F: (i am losing your voice...)

- F: a secret account

- F: not a time of purity

- Y: you are assigned a character

- Y: make the best of what was around

- Y: repurpose tools

- Y: continue gathering despite restrictions

- Y: staying connected to the community

- Y: think about who else may benefit from resources

- Y: recurrence, word of mouth gives rise to solidarity

- F: starting a month after

- F: confused joining, solidarity based on that

- F: a union with new people starting on chat

- F: it starts with someone needing a hammer

- F: it starts with someone needing a test

- F: it started with people having trouble paying rent

- F: it started with things that did not stop

- F: it started on tuesday

- F: a chat and doubt

- F: releasing documents

- F: organizing that starts with a stat

- F: chat

- F: it starts with breaking up

- F: intensity of seeing the fascists (not) go

- F: tech and having time

Refrain: "making the most of the hinge"

- H: waves of the lunch break

- H: closely connected

- H: what technology does in a particular situation

- H: not the generic one

- H: ongoing work

- H: being between many projects that are close too

- H: processing ways

- H: vernacular play

- H: collective moments of togetherness

- H: collective infra.. the act of doing

- U: hinge: capacity/ongoingness/different frames

- U: they get funds for doing ceretin kind of work

- U: on the one hand

- U: on the other hand

- U: not really a coincidence

- U: exchanging ways tactics for refusal

- U: at the same time have been really amazed

- U: they are just right at surface

- U: even though we don t see them

- U: are we funding these interactions

- U: feeding back into funding

- U: ////

- H: --live experience of the hinge--

- H: --reshaping one hinge into another---

- H: not a conincidence

- H: contradictions come with it

- H: if you decided to be the displacement between different places. people, you maintain this there is always contradictions you are holding onto something

- H: working as a hinge

- H: bringing it up

- H: rather than being an underground hinge

- U: different infrastructures were the hinges

- H: carries weight to make the movement possible

- H: out of proportion movement possible

- H: //////

- H: our relationships

- H: shock level

- H: shock crisis

- H: looking out for each other

- H: confidence of fascism

- H: ---

- H: spending money and how it creates oppositional to your wellbeing

- H: the school, the funding,

- H: how close to supporting this movement

- H: chicken sandwiches

- H: chickfill a funding inserruction

- H: where is my money being spent going

- H: to the radical institutions that work against me

- H: this moment has made everyone stop and consider where the money

- H: --- through the chicken s/w story---

- H: the hinge becomes visible

- H: by making it into a story you are making the most out the uncovering the hinge

- U: a lot of work lately, this mic

- U: there is no real prescription

- U: training in on sylvia winter

- U: (AI)

- U: these walls are problematic now with COVID

- U: we also need

- U: making people comfortable

- U: have to do something either way

- U: maybe classroom is the garden

- U: sylvia wynter is the hinge

- U: making the most of something

- U: even though crushed in this hinge

- U: we are gonna have to do something

- H: Sylvia Wynter as the hinge

Refrain: "making the most of the hinge"

- H: it seems important the awareness of the constraints

- H: as that isn't always there

- H: organsiing through fb there is a degree of accepting the problematic parts because the trade is neccessary

- H: it comes with a frame that might twist against you

- M: hinge that can empower to think beyond the frame/constraints?

- H: being aware that whilst looking through the different angles

- M: in this case fb is the frame, oraganizing is the hinge

- M: taking care of eache other during the demonstrations

- M: doing the right thing partially

- M: close to each other

- M: different ways of doing food distributions anyway

- M: big lineups outside

- M: everymorning a good morning

- M: daily hope og trying to keep hope alive

- M: started basic stuff

- M: impressed by the tenacity

- M: people were not allowed to gather

- M: and they did it anyway in didferent ways

- M: managed to do it in a way that was respectful

- M: deliver food

- M: families who couldn't make it or who had quite a lot

- M: emojis are undervalues [laughs]

- M: they have not given up on their families

- M: outside the scope of the state because it was needed

- H: not hiding for what is the basic keeping in touch

- H: sending hearts as a daily refusal of the state

- H: included laughter

Refrain: "beginnings that happen in the middle of things"

- F: always with these things

- C: angled points

- F: already important

- C: complicit kinship

- F: waiting not waiting not to be repatriatiated

- C: implicit level of technology

- F: accelerated means able to organise

- C: own lived experience with technology (as a shifting, trembling thing)

- F: being exposed to

- F: since it arrived it shifted it is different

- C: shifted by the pandemic

- C: crisis as a moment to atomise that does not lead to resistance

- F: when it is like that there is no resistance

- F: when it happened here

- C: similar things happening in other parts of the world

- F: when it happened in other places in the world

- F: when it happened on the street

The politics of listening

A workshop with Miriyam Aouragh and Seda Guerses

For our second round of approaching the conversations, we applied Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), again only involving companions that had been part of the conversations to begin with. As a way to decolonize our listening practice, Miriyam proposed a set of questions to ask while listening. This reflective methodology or reflexive ethnography was based on questioning the self, its power relations, its expectations and biases.

The “politics of listening” workshop was an inductive process of bottom-up interpretation, through making a socio-semantic inventory. Taking que from Decolonial Methodology, we felt that doing the research entails to give back to the phenomena or communities we study, which means that we not only take into account who pays for this research but also what purposes the research serves.

Our engagement with Decolonial Methodology was manifested in the way we designed the workshops, which themselves are entrenched in an ethical relationship between the researchers and researched. Our approach assumed accountability and therefore the research project had to involve reflection and reflexive writing which takes into account our own positionalities and biases. In this workshop we particularly played with the intersection between language and power, proposing to experiment with relation our own communications to politics. A politics of representation and the influence of subtext can come together in many ways, but few are as comprehensive for methodological interpretation as CDA.

CDA as a methodology emerged as an anti-racist method to delineate the discursive practices and linguistic features that construct the representation of social actors. We used its basic tools to apply it as a form of critical listening because CDA goes beyond classifying words and calculating common features. Instead the C = critical explicitly refers to its non-neutral agenda, which is meant to contribute to the change of a social reality by uncovering (with the intention of undoing) gendered/racialised/economic power relations and mind-sets:

- Gender/race/disability are predominantly assigned passive roles, but besides white/male/abled/middle class, also technology is ascribed with active disposition;

- Analysis about technological progress mostly foregrounds structure over agency, and machines over humans

- The moral framework or ethical scaffolding of a conversation can become clear when we unearth who are the most represented or the predominantly invisibilized actors in the discourse/writings/recordings.

It became clear that the speech pattern of circularity and friction was a way to hold together the conflicts and contradictions, and that this was part of understanding struggle. It made us wonder how to hold the concepts in relation to the experience that were being described, which feels necessary to then have an analysis of tactics and practice. We also discussed the implied linearity of the analysis, going from recording to transcript to memory, and how this might reinstate the figure of the expert interpreter after the fact.

An exercise in Critical Discourse Analysis

A collective exercise in critical reflexive decolonial orientations in listening. The exercise requires ca. two and a half hours, including a short break.

1. Split up in small groups (two or three people) and choose a conversation you would like to work with, and a channel to communicate.

2. Compile a list of terms that you think will appear in the conversation you are about to analyse. These can be common/expected/remembered terms. For example: infrastructure/technology, resistance/protest/activist, space/place, state, reactionary, capitalism/neoliberalism, racist/racism, funding/finance/money, ability/disability/ableism, feelings. (10m)

3. Search and listen: use transcriptions (e.g., search through the text) and recordings as a way to locate the moment that these concepts and themes occur, and select one or two moments where the concepts are discussed during the interview. (30m)

4. Ask how these concepts were communicated in the conversation (30m):

- How is the concept valorised or qualified (.... is shit):

- positive/negative

- hopeful-optimistic/hopeless-pessimistic

- accepted/rejected ...

- What is their temporality (in past present or future tense?)

- Can you detect a speaking pattern (hesitant, circular, trailing, in-out?)

- How is it spoken about (your own criteria for listening):

- silence/void

- agitated/enthusiasm

- ...

5. Compare notes between groups. (20m)

6. Look at other conversations for similar concepts and redo the analysis with both conversation in mind. (20m)

7. Social analysis: Frame what you found in discussion with other groups; consider the infrastructural, political, economic context of what is said/claimed/proposed. (30m)

Word2complex

A workshop with Varia (Cristina Cochior and Manetta Berends)

This workshop was a play on word2vec, a model commonly used to create ‘word embeddings’. Word embeddings is a technique used to prepare texts for machine learning. After splitting the writing up in individual words, word2vec assigns a list of number to each individual word based on what other words they find themselves in the company of. Once trained, such a model deducts synonymous words from comparing contexts, or will suggest probable words to complete partial sentences. With word2complex Varia proposed a thought experiment to resist the flattening of meaning that is inherent in such a method, trying to think about ways to keep complexity in machinic readings of situated text materials.

Step 1: Cutting embeddings of words

Choose a body of texts that you would like to analyse. Count how many times words appear in this text. You can use a custom script or an on-line service. Pick one word that appears at least twice from the list.

Step 2: Embedding words

Use CTRL+F to find your word in the text that you are analysing. For each moment in which the word is used: describe briefly the context in which the word is.

Examples

Word: street (wordcount: 2)

Embedding 1: street -> activism

- "We've been talking to people more involved in both intellectual and academic work on, for example, like Nadia on solidarity and Islamophobia, on thinking about colonial structures in organizing and activism on the street."

Embedding 2: street -> survival

- "From Brussels, the food collection was allowed so I think in the streets you had long lines queueing up of people. They managed to do it in a way that was respectful of the social distancing measures basically."

Word: companies (wordcount: 2)

Embedding 1: companies -> crisis

- "I think a magnitude level failure with our tax money, obviously, that went to their friends, but the collaboration around formulating and writing about extractivism, colonialism, settler colonialism, capitalism and how that manifests itself in moments of crisis like COVID, and the Shock Doctrine approach of companies and governments to implement things like track and trace and now probably also, what's it called certificate, of vaccine certificate."

Embedding 2: companies -> refusal

- "Then there was an ongoing boycott by left-wing people of the companies that closed their doors to protest this."

Step 3: Identify/generate/complexify relations

Pick two words that have been embedded (this can include words that someone else embedded). Expand the semantic map below and feel free to adjust the connectors (they are starting points, not prompts)!

Example

shitstorm -> war on terror - "In the meantime, I got sidetracked by the shitstorm that has been happening around us for the last 10 years."

violence is to policies as shitstorm is to war on terror violence is to a fascist street as shitstorm is to war on terror shitstorm is to war on terror not as the state is to context

Semantic map

______ is to ______ as ______ is to ______ ______ is to ______ not as ______ is to ______ ______ is not to ______ as ______ is to ______ ______ is to ______ as ______ is not to ______ ______ ..... ______ ..... ______ ..... ______

Infrables

A workshop with Varia and The Institute for Technology in the Public Interest

Infrables make negative use-cases and un-fixing bug reports as a solidary praxis. They are articulations of what extractive digital infrastructures are, and what they are doing. What infrables can we tell to take-down Big Tech narratives and undo their violences? Generated through narrative and extra-narrative accounts, infrables identify oppressive infrastructures or tools, but they also make space for other technological attitudes.

How can we follow and understand infrastructural shifts through shared experiences? To what extent do individual experiences stand for a larger whole? What happens when you share, retell, adapt, rewrite someone else's experiences?

For a growing collection of Infrables brought together in different contexts, see the booklet here: https://titipi.org/pub/Infrables.pdf

Part 1: Infrastructural anecdotes

- Bring an instrument. Maybe you find yourself in a room with a guitar. Or some pots and pans or any other set of objects that can make variable noise.

- Pick a few anecdotes from the collection and read them out loud. One or more listeners accompany the readings with dramatic sound effects.

- Once the reading is done, work in small groups and tell each other a story or anecdote of an experience involving a digital infrastructure. Take 10-20 minutes to transcribe; give each anecdote a title

- Pick a few anecdotes from the new collection and read them out loud. One or more listeners might accompany the readings with dramatic sound effects.

Part 2: From anecdote to infrable

- Form groups of 3-5 people.

- Each group picks an anecdote. You can also mix several anecdotes.

- Gather on an etherpad page if remote, or meet around the table if your infrable-session is IRL.

- Choose some elements, and a format (see below).

- Re-write/change/re-tell the infrastructural anecdote into an infrable together.

- Pick several anecdotes from the collection of anecdotes and read them out loud. One or more listeners accompany the readings with dramatic sound effects.

Infrabling elements ✨

- Make the intention (instead of the "moral") of the story explicit: what is the intention for the "public interest"?

- Introduce a maxim, "concise expression" or motto

- Introduce fictional agents, such as talking plants, inanimate objects or other creatures (e.g.: the tortoise and the hare, grasshoper and the ant, etc.)

- Make space for natural phenomena, machinic agencies, other animacies

- Scale the timespace of the story

- Infrastromorphise (instead of antropomorphise) agents: attribute infrastructural characteristics, motivation or behavior to inanimate objects, animals, or natural phenomena

- Use rhyme, rhytmn and repetition to rewrite/retell the anecdote

- ...

Formats

- A drawing

- A shared BigBlueButton whiteboard

- Some pad writing

- A spoken story

- A song

- A poem

- A fiction

- A slogan/T-Shirt

- ...

Infrastructural anecdotes

Hanging there

When I arrived here at Rotterdam I remembered a friend of mine from long ago was living here somewhere. I have shut down my Facebook a few years ago but I had to reopen it cuz I had no other way to get in contact with her. When I did it, I found my profile intact, outdates and it creaped me out, but worst was to see and decide if I should read or not old messages from friend and colleges, job offers, favors and happy birthdays hanging there unanswered. I left as soon as I could.

What if I was not fit?

I remember that every time I wanted to register for a COVID test via the website I would always get options to get tested in random places, often far away from where I live. That was despite the fact that I marked the option that I cannot get there by car. Even though I did not always feel fit to get to the test location, I am a young and able-bodied person. I kept wondering what happens if you are not as fit? Why were there no more options presented? it was different when you registered for a test by phone.

Sentimental download

A best friend from high school passed away many years ago. We both used Xanga as a blog/journal during our high school years, and used the private messaging system essentially to joke at eachother back and forth - empty chats. Xanga messaged me when they were shutting down in probably 2014... or earlier? asking if I wanted to download the text code of my page. I did, and in the bundle was also included my and Stephanie's private correspondences, hidden comments, hidden posts. This is a moment of tension, perhaps grief (two years after her death), but also sentimental.

Check-in

The phone I use is quite old and so I could not download the national tracing app. I therefore could not access some locations as I could not "check in" digitally. This was during the first lockdown, but it seems that since then venues have been told they could not discriminate against people without the app and to offer alternative (paper) check-in processes.

Faceless

In the work that I do the organisation uses Microsoft Teams. In the first meetings we had I didn't want to install the app or program on my laptop, and so I joined straight from browser. It took me some meetings to realize that that was the reason why I couldn't see my colleague's faces, because the software allows you to see other people's faces only if you install the program.

Domestic vulnerability

Out of curiosity and of enthusiasm, I am running a small chat network from the meter box in my home. It actually is connected to an electricity plug right under my bed, so sometimes when I hover the bedroom and I touch the plug, the whole network goes down. A small form of domestic vulnerability. But anyway, the network runs most of the time.

Lost letter

My flatmate received COVID support during the early months of COVID, since she was unable to work in either of the two jobs she had. She applied for it, unsure about the conditions, even though she was fulfilling the conditions. At some point we received a letter from the government that was unfortunately misplaced & buried under some newspapers we receive from our neighbours when they are done with them. Because she hadn't seen the letter within 2 weeks and because she hadn't responded she had to give back the entire sum. We assume the reason why the letter wasn't also sent digitally was to check if she was home during this time.

Overheated laptop

During the pandemic my laptop is suffering so much. It is getting a bit old (not even that old), but videoconferencing is so tough on it. I am not a professional participant in video conferences, not being able to use background images, sometimes accidentally logging off because my laptop got overheated.

Vaccine bro's

So people doing sexwork were saying to me, "do you have the vax badge on your profile", and then others were asking "have you seen the taglines on grindr", people are labeling themselves as big bear Pfizer, as Moderna otters, some said they saw a profile that was labelled, let me check it was ... yes: "Grindr profile of a “vaccinated top” with the foreboding caption, “It has begun.” It’s inevitable: the antibody bro is about to become the vaccine bro".

Corona 'Help'

With the first Corona aid, you could get 5,000 euros and there were people who got that. There were also people who took money fraudulently. That's why people had to give it back. Most of the people I know have actually transferred the money back. Because it is not clear at all. And there is so much stress. It's so unclear. You are being criminalised very quickly. People then immediately make a case of fraud. At the beginning it sounded as if it was available to everyone and you had to apply for it very quickly. You only had a certain amount of time to do it. I think it was 10 minutes or so and then the page closed. But the problem is, only if you received a number, you can get to this page, you've been waiting for days until you can get to the webpage. And I also have to confess, I didn't read the small letters, I just saw "I can get money". So they asked "Do you need more money?" and I of course said "Yes!". I wasn't entitled to that much help, because it was only for operating costs. But I didn't read the instructions. I was just trying to get my turn before Berlin said they had no more money. Because after that there was a time when it was stopped, because there was no more money. And now it's like this, you need to pay it back in one go. But it's not clear who pays back or not. And every tax advisor says something different about it. It's the same with friends. But then you are criminalised. As if you did it consciously. I was in such a panic because it was clear that we wouldn't get any money for 4, 5, 6 months, that at first I just clicked, I need money, I need money, I need money. But it's already true, the billions that are paid out to the big companies and what is then made out of these small amounts. It's all pure neo-liberalism.

Self-managing a demonstration on Eventbrite

So normally I try to participate in the 8th of March activities either go to march, or join a demonstration but this year it was not allowed to go out onto the street in groups. So I was looking on-line if there were any activities planned and then on one of the websites that normally has calls for the demos, there was an announcement that the organisers had permission for gathering a hundred people and that you would have to sign up on Eventbrite so that the tickets could be distributed. Actually, it wasn't Eventbrite, but I think for the story it doesn't matter. So I clicked on the link and of course all tickets were 'sold out', like already they were 'sold out', of course. So in the end I joined another activity and ended up on the same square on which these 100 ticketed people were supposed to gather. I realised they had blocked off with tape ten areas for 10 people to gather, and had rented metal barricades - the cattle thing, they had a made a circle with these barricades so inside there were these sections for ten people each so it meant that the organisers of the feminist or women's march had self organised this idea of checking who had signed into the Eventbrite, maybe they would have a barcode scanner at the entrance to this zoned off area. But what had happened is ... I had joined a less official feminist bike ride, we were so many we flooded the square so the whole setup crashed - people were crashing through the gates, broke the tape, there was a mess of bikes and people, it was a mess, there was no way the organisers could have kept with their promise of managing their crowd. So the worry about the barcode scanner being put in place, the fact that everyone participating in the official march had given their name, address and email, is really scary and the fantasy of becoming its own police force that the organisers held was really scary -- from the setup you could see they thought they could manage it -- and then the white punk girls just crashed it.

Spitting with couriers

I was traveling - trying to travel to Brussels to see my comrades and I was very anxious. I had ordered the COVID test and downloaded the app. There was a technological hitch and so it arrived two days late. I was anxious about the test not being testable, that it would be a non-viable sample, so I rang the company and they said "It is good to keep the sample as fresh as possible", and so I could book in a courier between 08:00 and 18:00, that would come and take my sample to the lab. But they could not give an exact time. As fresh as possible! They told me to wait until the courier arrived, knocked at the door and to spit into the tube whilst he waited. He arrived at 13h and knocked on the door and he waited while I watched the video, and spit in the tube. Wait, I had to go through the app stages. Open the tube, scan the barcode, watch the video, whilst he was waiting. I then sealed the sample and had to put it in a transparent bag that I handed over to him and at that moment we had eye contact, as I passed him my tube of spit. At that moment I thought: is he my nurse?

Infrables

┻━┻︵ \(°□°)/ ︵ ┻━┻

In the work that I do the organisation uses Microsoft Teams and Zoom, no it was Teams I think, whats the difference? In the first meetings we had I didn't want to install the app or program on my laptop, and so in first meetings I joined straight from browser, the Teams, or Zoom, house party, Jitsi or was I on Tiktok? I dunno... In the first meetings I was just staring at the icons, wondering why everyone was refusing the camera. In the first meetings even the head of the organisation didn't have a camera. In the first meetings I was still working but I gradually just relied on no camera too, taking the meetings from bed, from the floor, from wherever i felt the fuck comfortable. It started to really change the work I was doing, and i started to dream of the abolition of work, I mean before when we all had to sit in those team meetings and see each others faces, all encouraging each other too work. I mean I started to build like a beavers den or a like a badgers burrrow near where my desk would be, at one point I just took the desk broke it down, and burnt it outside. I mean I started to do my spreadsheets as if I was a beaver and before long I pretty much realised beavers don't care about spreadhseets. It took me some meetings to realize that that was the reason why I couldn't see my colleague's faces, because the software, that I think it was Zoom, or Jitsi, or was it that time i got invited to queer haus on mastadon no sorry it was Team I guess , allows you to see other people's faces only if you install the program. I had only Facetimed with my mom once a week until that day and she could see my burnt desk. You know when your mum answers the videocall and you still cannot see her face because the phone is so close to her face. what if I hadn't seen their straight faces for the last 12 months? - I think I rather not have seen my colleagues faces all semester, sleepy or full on make up on and showing of pajamas and eye bags, but mostly my own nap face was there. During the months of not seeing my colleagues faces, their faces slowly changed. After the installing, trading space on my device for faces, their motion changed. What ever happen to phone calls?! No file to safe after, no records, tracks... Im so paranoid this days, it really freak me out. I never got the invite for fucking Clubhouse. ◕ᴥ◕

Melting your CPU, one meeting at a time!

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Melting your CPU, one meeting at a time!

A stab in the dark at team building

__..--\

__..-- \

__..-- __..--

__..-- __..-- |

\ o __..--____....----""

\__..--\

| \

+----------------------------------+

+----------------------------------+

+++++ micro ++ soft ++ protest +++++

+ against the unequal distribution +

+++++ of terms and conditions ++++++

Join us in the blackout room!

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Proxy Power

Once upon a time, a device who was relied on heavily began to age. It took them longer to feel a tap, even longer (more forever) to use an app. And even worse, (access to THE SPACE denied)

Other phones that were also aging, had other issues but felt more and more annoyed and frustrated, so they met up one day for a big cup of coffee... With cracked screens and lint-filled ports, they decided together that they needed a new kind of power: PROXY POWER.

Characters:

- The Old device

- The Newer device

- The hero (a caring relative)

- The villain (state employee)

- The user (may or may not have covid)

- The space (the user is trying to access)

- The digital infrastructure

Addressable targets

"Addressable targets do not always receive what they deserve"

What have you given up to technology in the name of safety?

What have you given up to technology in the name of safety? How has this affected you?

We are asking these questions to our friends who sell sex as a gesture to provoke further inquiry into how life maneuvers within and around technological apparatuses.

Sex workers are on the forefront of harnessing technology as a popular tool to interrupt surveillance and evade the violence facilitated by technology. Of course, we want to be safe, but we do not look to any external designation of safety. Despite all our tricks, masks, and hacks, we are profoundly affected by the state’s deployment of data aggregation, regulation, and threats. It is hard to think about what we are building in resistance when there is so much being done to us.

How often are we asked to cooperate now so that later we can be free? Work is never safe. The money we gain offers a chance at stability, and the prospect of sharing what we might then build with others - this is why we have found ourselves here at all. But what have we given up for that money?

Are we so resigned to surveillance in our other crimes? Where is the call to be boundless? Where have we stagnated in an attempt to master the algorithm? There is no action but the action we will.

After hooking for a decade or more, any semblance of romanticism I take in my work has faded away. I do not like work. And I certainly do not like sex work. But it is the best of worse options for me. I have a criminal record. I blur my face in all my online advertising. In the beginning, sex work allowed me to survive, and eventually thrive with essentially zero trace to my actual identity, and in spite of how employers would not hire me because of my record or lack of higher education.

But over the last decade, Slixa and Eros among other online advertising sites I use, all began requiring some kind of identity verification in order to advertise services. I sometimes catch myself short of breath knowing my driver’s license is just a hack or a court order away from being associated with everything I have ever linked with my hooker name on the internet.

I signed up for OnlyFans at the beginning of the pandemic. I am now back to working in person but continue to receive about $100/week from OF. So, when they started requiring a new verification process for all content creators in 2021, I was relieved. I thought I finally had an excuse to get off this wretched site; I hated the thought of exchanging a biometric scan of my face for the ability to sell content. But when OF refused to allow payouts to my bank account until I verified with the third-party service Ondato, I watched my unclaimed balance grow, then I caved.I find a little comfort in knowing I wouldn’t be alone in facing the fallout of, for example, a mass hack of Eros or OnlyFans. But it all pales in comparison to the potential nightmare of facing my neighbors, my landlord, and others if my identity were to be released. It feels like I am participating in my own doxxing. Whatever social legitimacy I initially exchanged for anonymity in sex work a decade ago is now ten-fold in its potential cost to my livelihood.

— Harla City (Southeast U.S.)

The most popular escort directory (Adultwork) here in the UK requires its users to submit selfies with their ID in order to maintain a profile. This was already the case but we all received an email recently reaffirming this policy in light of the same Mastercard policy change that wrecked havoc with OnlyFans. Being able to use this directory gives me the safety and benefits of working indoors and independently, where I can get in contact with and screen my own clients. The financial security that I’ve gained from sex work over the last few years has been one of the most transformative things in the last few years and this definitely makes me feel ‘safe.' At the same time, sharing my passport details with these platforms makes me feel incredibly vulnerable. They have readily available access to my identity and as good as proof as any that I’m a full-service sex worker.

Selling sex indoors and independently (i.e. not in a brothel, managed premises or venue shared with others) is legal in the UK. However, I feel scared knowing that if the laws around sex work changed in the UK, Adultwork could be targeted and a situation like the raid of Eros and Backpage in the US could occur. Even if the law doesn’t change, there’s a ‘chilling effect’ of criminalisation internationally.

I worry I may not be able to enter the US and visit family because of the extensive digital footprint that implicates me as a sex worker. The US Department of Homeland Security has been known to deny entry to and ban suspected to be sex workers on the basis of their internet presence and online advertising.

— Simone (London, UK)

Technology, or more specifically the internet and how media spreads on it, has at times ravaged a sense of my own safety. Various forms of my personal information have been circulated beyond my control, leaving me in a state of over-exposure, all while twisted constructions of who I am or what I do as a sex worker swarm from the minds and keyboards of online bigots. The internet can act as a tool to over-sensationalize, and the internet does not consider real life reactions outside of its machine. Backlash to this skewed information about me has at times been aggressive, obsessive, and violent, all affecting my mental well being, as this information carries on in the form of real-life labour to protect myself from the tired and regressive narratives that orbit sex workers at all times.

— Mistress Rebecca (London, UK)

The further social media progresses, the more it requires of sex workers. And the temptation to have a presence grows. I’ve sacrificed many social relationships and potential work relationships by being coerced into publicizing my work as a stripper, only to be reminded that it’s actually not safer or more lucrative.

I created social media and OnlyFans accounts under alternative aliases as a method to prevent sharing my cell phone number or personal information with clients. I’ve also used alternative phone applications to create fake phone numbers to route through my phone. Doing this provided the perfect opportunity for a client to stalk and threaten me both virtually and in person through basic internet sleuthing. Both my Instagram and OnlyFans, which I thought would give me the safety of anonymity, were hacked in their own time.

Additionally, the attempts to preserve this anonymity from my clients actually required me to upload explicit content that is now owned by Facebook, Instagram, and Google, which will be used for their own algorithms, sold for marketing, and can be sourced by the state. The programs will also be using my information to create even stronger surveillance techniques, which will, in the long run, kick me off of these applications, and fully prevent sex workers from using them in the first place, putting us at risk for being targeted by the state.

It’s like companies are using sex workers as guinea pigs for innovative applications functioning under the guise of safety, but eventually, they are sold to surveillance companies that turn around and throw us in jail.

— Zoe (Chicago)

The censorious algorithm, adversarial ‘machine learning,’ and privacy-and-identity surveillance, are three recent technological modes especially equipped, already devoted to, hurting whores. These are built on logical threads that continue to de-weave and re-tangle themselves, rendering and refining their own capacities through endless iterations. It makes sense why they would become a whore's obsession.

The screen seduces us, threatens our focus out in the world. The promise of safety: technology protecting us from preventable suffering. But Technology and Sacrifice are inextricable. To acquire one form of innovation or knowledge, we end up, inevitably, rescinding others. Sacrifice implies both forfeiture (what I give up) and resignation (what I give up on). Our work consists of real time speed trials - stakes driven by what we know and what we can’t.

I forfeit my energy to the time, and mind sink, of the internet. I expend many living hours researching technology, imagining I can know just enough to protect myself and my friends. Obsession here is as addictive as any chemical cascade; through the labor of trying not to panic, I’m developing a tolerance. I derive comfort in technology’s many failings, a horror-comedy of smart houses turning against their owners, grotesque-surrealist digitally rendered genitals, AI chat bots getting caught cheating, the fem-bot painting herself.

We fear that doing this work will make us lose our lives. Like logic, fear aggregates and compounds, so much that we risk losing our minds, and the technology fulfills its intents. I resign myself. It’s a fact - if someone is determined enough to hurt me, they will. Presence is our only real protection. I return to my senses.

— Lyn (New Orleans)

I started working after I connected with a random little cluster of hustlers. I learned from them, and mirrored their practices from advertising to screening to cultivating a protective intuition. What this meant in practice was that we used the most basic and accessible advertising platforms, making bare-bones posts, sometimes with just a few sentences and a photo of someone who represented our race and general appearance. On some level I had already drawn a line that I didn't ever want to fully connect my image to this work. Those mediating data points, my IP - used to place ads, or phone records, or a 4th, and 5th email account that are connected to the 2nd and 3rd, also connect my identity to my activity, albeit a little more indirectly.

Is my identity linked to this work? Yes, but perhaps not through biometric proof. Does that make me safer? I don't know - safer from what? Sw’ers are stuck between mortal danger of bodily harm, legal danger of prosecution and its aftermath, long-term psychological harm from adverse or transgressive experiences, and the list goes on. The constant weighing of the scales is itself a burden to bear. The decision to separate the image of my body from my advertising is partially informed by the fact that I feel like my body itself is more easily identifiable than others. What that exchange has meant for me in practice is that I also have to bear the psychological burden that comes when, in preserving some meager, but ultimately false, sense of safety, I have to deal with an occasional client who interprets unoriginal photos as a manipulation against them instead of a protective measure that I claim, despite them. That's no fun - clients feeling entitled to be critical of your body, your dress, the competency of your presentation. The stoicism or nihilism or void I've gained from these kinds of singular experiences through sex work alone is interesting to me. Anyway, the other tradeoff is that using these basic advertising platforms that permit a degree of anonymity sometimes means encountering more unpredictability with clientele. The impression of an added layer of safety from the biometric memory of the state has at times left me square in the middle of differently unsafe circumstances, probably the worst case being huddled in silence with a handful of other women, separated from a duo of aggro robbers, or potentially violators, by nothing more than a shitty metal lock.

— nana (U.S.)

I have given up my face, my government issued ID, my name, and some sanity, all to work online and have my profile verified by the companies who require me to do so. This is accepted as a sex worker’s wager for safety — supposedly anything is better than working on the streets, or at least anything where you can be given the illusion of having autonomy.

Sometimes I still think of where all of the hundreds of hours of footage from camming are now, having been recirculated in 3rd party markets, and wonder if there will be a day when they will resurface in a context I won’t be able to ignore.

Or times when I used part of my face in ads because I knew it was another kind of necessary currency, and I needed it to sell an image I was trying to portray. Plus, I needed money fast. In the end, I knew it wasn’t worth it — intensive political repression was amping up in my city, coinciding with an increase in prostitution stings, and I didn’t want to find myself in the crosshairs.

Later, I exchanged my legal name with certain long-term clients to escape the techno-surveillance of ad platforms, camming or sugaring sites, etc. Then they could buy me plane tickets or put money straight into my bank account, all while crafting a plausible paper trail that could be used either for my benefit or against me. This is potentially the greatest threat to my safety, but also one of my greatest rewards -- to escape the hustle of marketing, visibility, social media, a website, and ads. These are the things I have always hated the most.

Even though this more intimate work of sugaring can feel like punching an emotionally-saturated clock, I recognize a difference in these spaces between work and not-working. When maintaining a crafted hooker persona, on the other hand, I never experience the feeling of being "off-the-clock", since I am basically my own small business. The measures I needed to take were for that wager between safety and sanity, knowing what both could hold, either for, or against me.

— Ana (U.S.)

As a dancer who has worked primarily in strip clubs for the past decade in person, surveillance technology introduced in the name of safety has negatively affected my sense of autonomy and security. Despite popular narratives around working conditions and contracts in clubs giving workers more job security, the safest I’ve personally ever felt is working under a fake ID in a club with no cameras. This club didn’t take my fingerprints, SS #, inquire into my address, or track the money I was making in an internal system. At most clubs now, I am required to provide all these things in order to get a contract, which can then be terminated at random, while my biometric data and personal information remains in the club’s system. Typically, there are security cameras surveilling the dancers in the dressing room but not in the VIP booths, suggesting our coworkers are more of a threat to our safety than customers behind closed doors. Clubs that increasingly track my dances and stage time in centralized systems have a better ability to charge exorbitant shift fees. The increasing surveillance in the clubs in the name of worker safety has always felt like a sham, leaving me with less autonomy and more ability for the club to control and exploit me further.

— Aiden (U.S.)

I cycle through about ten aliases. When I was doxxed for political activity seven years ago, I lost the use of my name after death threats and repression. My name is entombed on the internet, I leave it there. Anyone is a google search away from knowing it all, this has been proven to me many times. One thing leads to another.

I have uploaded my state ID, passport, full body photos, my face next to the daily newspaper, fingerprints, to various technologies in order to sell sex. Though whenever I go to see a client, I leave anything with my name at home. When I am home I try to keep my devices separate, try to understand all the invisible linkages, try to not hate myself when I inevitably fail. Or when I am recognized in the gym, the classroom, the street.

Criminal activity aimed at making money requires arbitration and enforcement of illicit agreements to advance. So, you trade the supposed danger of isolation and the uncertainty of free-styling for these platforms, which transform what you once dealt with into new forms of capture. You must make a deal with someone, pimps, the IRS, often both.

Living often requires criminal activity, with life being so crushed by power. Whoring came to me when I needed money but failed background checks. It’s something I know how to move through, make gains, shape to my own choices. But it also pervades all aspects of my life, often fills me with dread or the ugliness of all I do in the pursuit of money. So it is hard to know if it ever positions me to engage in more joyous and revolutionary clandestine activity, or puts these efforts at further risk. My life has lead me away from citizenship, away from identifying myself, away from sacrificing my body toward mediated desire. If I am oriented against the state, how do I reckon with the concessions I have made to accumulate money, other than putting that money to our use?

— Star (New York City)

Following these responses, we came up with some further questions for our readers, sex workers or otherwise, to consider —

1. What have you given up to technology in the name of safety? How has this affected you?

2. Where does sharing our (SWer) experience, in writing, in poetry, in collaboration or panels, leave us more free? Where does it lead us to a dead end? In whose company? Apply this to your own life if you are not a worker, or, ask a worker you know.

3. Imagine a world where people don't die for being whores, aren't tracked, aren't prosecuted. How do you fit in? What can you do to create or preserve this world?

4. As workers, we secure our marketability via the realm of the explicit. What we orbit around, though, are the subtle possibilties held within unnameable, sensual, living desire. What do you see the state making us desire? What desire, what pleasure, will never be regulated by the state?

5. What role does the state have in your fantasies?

Other Weapons is a site for amassing and proliferating knowledge, stories, and positions by sex workers. It has no set place, but circulates in the form of printed zines, online pdfs, emails, stickers and wheat-pasting, and occasional public appearances. Our aim is to experiment with sex workers and our accomplices toward material strategies for our autonomy and liberation. We are for finding life outside of any given parameters, for finding ways to live, interdependently, beyond survival. Through print material, discussions, letters, film, music, and visual work, we attempt to distribute intelligence often hidden or unpublished.

Cite as: Other Weapons. 2022. "What have you given up to technology in the name of safety? How has this affected you?". In Infrastructural Interactions: Survival, Resistance and Radical Care, edited by Helen V Pritchard, and Femke Snelting. Brussels: The Institute for Technology In the Public Interest. http://titipi.org/pub/Infrastructural_Interactions.pdf

Impossible Breathing Modular Meditation Praxis

Clareese Hill

Welcome to a modular meditation praxis. This meditation consists of three materials that can be configured for the meditation you need at the moment. The first element is the meditation room, which is an immersive web space where the other two materials can be experimented with. The second material is the content for the meditation interventions. The content includes audio from seven singing bowls as they correspond to the seven chakras and poetic text by Black woman writers. The third material is the core meditation text which has moments for interventions of sound and poetic text. There is no order or prescription for how the meditations should unfold this is a space of poiesis.

1. The meditation room is where you can hold your meditation by bring the other three materials into that space. The meditation room is web virtual reality experience that is editable by watching the tutorial video found below under Mozilla Hubs tutorial. The meditation room can be accessed by the QR code or the links below.

- Mozilla Hubs Impossible Breathing Meditation Room: https://hub.link/Q6SDo39 This is where you can conjure your meditation. Mozilla Hubs Room code: 286185

- Mozilla Hubs Tutorial - Instructions on how to add the meditation interventions to the Mozilla Hubs meditation room. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5QnOsyyebEQ

2. Content for the meditation interventions: http://titipi.org/projects/impossible_breathing

3. Core text to be treated as fluid as water:

Impossible Breathing

Let’s take a breath

Let’s be still expect for our breath

Let’s let everything wash away with every breath

Inhale

Hold the air as breath, feel its contribution your body

Exhale

Let’s be slow together

Let’s meet in-between the inhale and exhale

Let’s meet in the air we hold as breath

Let’s image what it would be like to sit next to each other

Feeling each other’s energy becoming still

While we breathe together

Let your body go in this moment and the contiguous we will share together

Its’ no longer needed to be legible

Let the performance that the body is automated to engage in slows to a stop

We are connecting through our breathing

Being together through breathing

Feeling each other’s touch through breathing

A together that defies the constructs of reality

Insert Intervention

Let’s make right here right now abstract through breathing

Let’s participate in a contra-reality together that we conjure through our breathing

Let’s be there for each other and support each other with care through our breathing

Let’s think about meeting in-between the inhales and exhales

A liminal space that is unprescribed.

A multifaceted dimension of everything we need

Let’s take a journey of errantry together from the cosmos to under the surface of the water

Let’s learn together to practice impossible breathing

Breathing that happens outside of the reality, the landscape, the body, the lungs

Outside of the linearity of the rising and collapsing of the chest

Insert Intervention

Let reclaim our relationship with the water

By learning from the waves, the currents, the aquatic terrain, and the wise inhabitants

They are griots of futurity

They ask us to sit with them so they can tell us stories of duration, resilience, and poiesis

Let’s learn from the water by being fully submerged

And still breathing without water entering the body

Breathing in errantry is a shift towards nonlinearity

Nonlinearity requires a skip around in the in process of breathing first as thought then as praxis.

Insert Intervention

When our attachment to reality has uncoupled

Through being submerged and still breathing

Impossible breathing

Our residence, where we are occupying is thrust into the slippery the in flux

A residence that is under the surface

Our residence is the arrival to a space, a moment, an intention that has always been with in grasp through being able to disrupt our breathing

All we had to do was let go of the landscape and reach for the water, through the praxis of impossible breathing

Cite as: Hill, Clareese. 2022. "Impossible Breathing Modular Meditation Praxis". In Infrastructural Interactions: Survival, Resistance and Radical Care, edited by Helen V Pritchard, and Femke Snelting. Brussels: The Institute for Technology In the Public Interest. http://titipi.org/pub/Infrastructural_Interactions.pdf

Notes Towards an Antifascist Infrastructural Analysis

Gwen Barnard, Naomi Alizah Cohen

‘The infrastructure of fascism is staring us in the face’ - Arundhati Roy (Roy, 2020)

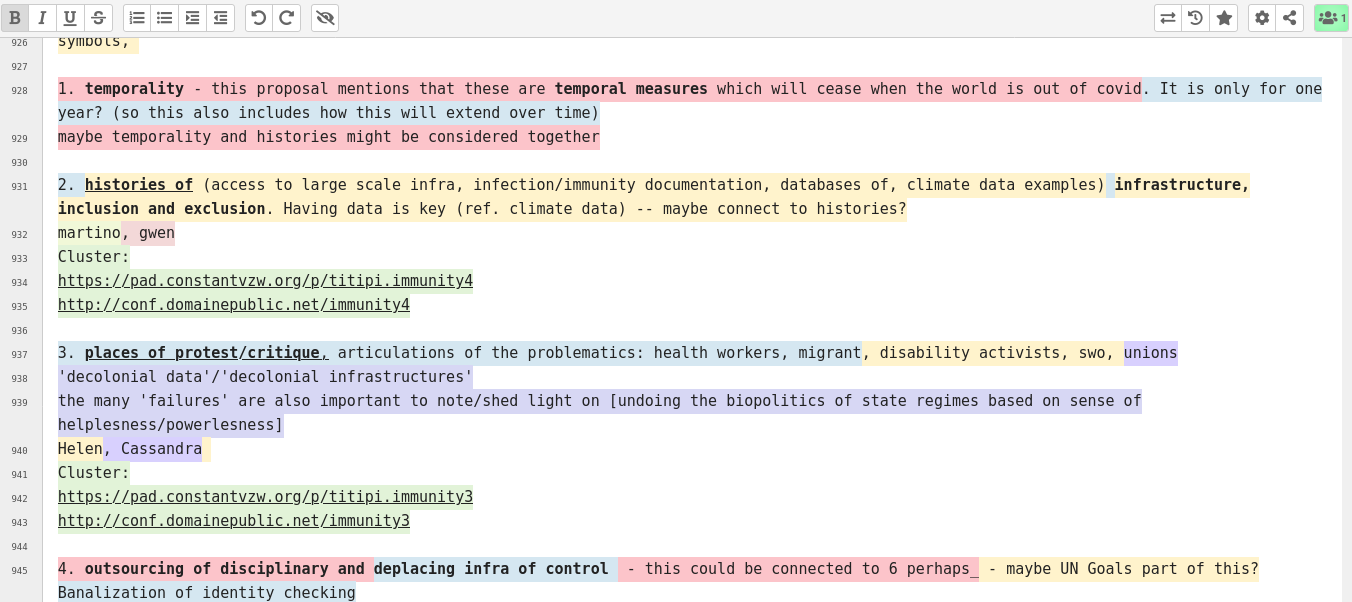

Introduction