Spellbreak training: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

Wayfinding through portals is rarely done alone. Instead, this is a collective movement, a shared process where organisations accompany one another through uncertain terrain—a process that can play a dual role, facilitating both change and accountability. Granted, not everyone will step through the same portals at the same time—or in the same way. Some may sprint ahead, others may hesitate. Some may be able to implement structural change quickly, while others must move slowly, negotiating their own specific contradictions and constraints. The imperfection of the spellbreaking process is not a deterrent; rather, it needs to be understood as a feature that reminds us of the need to constantly assess and re-evaluate the direction we choose to take—with the understanding that this might, at times, approximate one actor to another, and in other times result in divergent paths. This asymmetry is not a failure—it is inherent to the ecology of collective divestment. | Wayfinding through portals is rarely done alone. Instead, this is a collective movement, a shared process where organisations accompany one another through uncertain terrain—a process that can play a dual role, facilitating both change and accountability. Granted, not everyone will step through the same portals at the same time—or in the same way. Some may sprint ahead, others may hesitate. Some may be able to implement structural change quickly, while others must move slowly, negotiating their own specific contradictions and constraints. The imperfection of the spellbreaking process is not a deterrent; rather, it needs to be understood as a feature that reminds us of the need to constantly assess and re-evaluate the direction we choose to take—with the understanding that this might, at times, approximate one actor to another, and in other times result in divergent paths. This asymmetry is not a failure—it is inherent to the ecology of collective divestment. | ||

In this context, gatherings—ritual, joyful, mundane—can become points where concurrent processes of orientation, reorientation, and disorientation take place. What would it mean to throw a party where attendants can leave Instagram together as a way to collectively soothe the insecurities that come with the divestment from a platform that promises exposure, attention, and connection but is ultimately implicated in systems that harm all forms of life? What kinds of insights could we gather on the meaning of attention, exposure and connection, and what alternative forms of operating could we conceive, stemming from those new formulations? | In this context, gatherings—ritual, joyful, mundane—can become points where concurrent processes of orientation, reorientation, and disorientation take place. What would it mean to throw a party where attendants can leave Instagram together as a way to collectively soothe the insecurities that come with the divestment from a platform that promises exposure, attention, and connection but is ultimately implicated in systems that harm all forms of life? What kinds of insights could we gather on the meaning of attention, exposure and connection, and what alternative forms of operating could we conceive, stemming from those new formulations? | ||

Revision as of 12:25, 14 June 2025

Spellbreak Training: A peer-to-peer cloud divestment network

Spellbreak Training is a proposal for a collective, peer-to-peer process of divestment from what we call the Regime of the Cloud—a techno-social amalgamate of tools, infrastructures, devices and modes of doing that produces harm to all forms of life. This regime establishes modes of governance that structure and regulate behaviours, reconfiguring our perceptions of subjects, infrastructures, and territories along colonial and capitalist hierarchies.

Introduction

Spellbreak Training is a proposal for inter-organisational coaching meant to foster coalition and community for small institutions and spaces interested in divesting from the regime of the cloud. Undertaking such a transition implies a fundamental reconfiguration of the ways in which a small organisation functions; it is a process that demands patience and attention, and in so doing allows those involved in the process to ask fundamental questions around the institution's own goals, interests, desires, ethics, and orientations. The training was developed for and with organisations working in art and culture, but could easily translate to other fields.

Cloud divestment is an important—though often overlooked—point of action for spaces committed to social and environmental justice, as well as to all forms of anti-colonial struggle. Big tech companies are implicated in practices that provoke deep, sometimes irreparable harm to communities and landscapes—from their involvement with mining and the depletion of natural resources, to their enthusiastic leadership in the development of military technologies that cause immense suffering and are instrumental to sustaining colonial order. The cloud, both as material and symbolic infrastructure, stands at the core of these operations. It is through the cloud that Big Tech companies are able to buy and sell data, train AI agents, and fine-tune advertisements to more effectively target their users. On a deeper level, though, the cloud can also be understood as playing a key conceptual role: that of sustaining the capitalist illusion that infinite growth is both sustainable and achievable. It is a proposal that seeks to interrogate how the computational frameworks that underscore the daily operations of a small organisation are entangled in genocidal structures, and imagine alternative, anti-colonial approaches to technology. Divesting from cloud infrastructures means, then, undertaking a process that requires an examination of our limitations—as individuals, as well as community members—as well as the limitations of our landscapes and resources. It is important to note, however, that limitations do not have to be equated with scarcity. Rather, the divestment process can be approached in fun, playful ways that nurture other forms of resource wealth, which can then be deployed when necessary.

This proposal was first developed through a conversation and experimental workshop between Luiza and Femke (TITiPI), and Ailie (Market Gallery and FEN), which took place in Brussels in the spring of 2025. The idea for Spellbreak Training began with a request emailed by Ailie to TITiPI. As a member of the board at Market Gallery and co-director of the Feminist Exchange Network (FEN)—both Glasgow-based—Ailie expressed concern about the use of technologies complicit in the ongoing occupation and genocide in Palestine, which stood in direct contradiction to the solidarity statements released by both organisations.

'In light of the ongoing genocide in Palestine and our commitment to the BDS movement, the gallery is considering a more ethical model for a) financial management, withdrawing custom from Bank of Scotland, and b) data storage and digital archiving by moving away from ephemeral archive systems that are housed by corporations such as Google and Dropbox. A more ethical method of data management is in creating a private online server for the gallery' (statement on the Market Gallery website)

A House of Mirrors

Many of the concerns and anxieties this proposal seeks to address stem from the challenges affecting art and culture at the point in time we are writing this from, in the spring of 2025. We believe that these challenges not exclusive to cultural organisations; rather, many of these issues reverberate across other fields of knowledge and practice. Some of these concerns include, but are not limited to:

- the harsh funding cuts that have negatively impacted many publicly-funded organisations over the past few years, particularly those working towards various forms of social justice and human rights;

- the scarcity of time, energy, and other vital resources that these funding cuts create, particularly in fields like arts and culture, where workers are already chronically overworked and underpaid;

- how algorithmic presence has become a metric for an organisation's relevance, importance, and most importantly, access to already-scarce public funding;

- the sense that divestment from cloud technologies will negatively and severely impact the internal workflow of the organisation, as well as hinder its ability to connect to external collaborators and its public.

Given this context, a call for divestment from cloud technologies can trigger significant anxieties and uncertainties around the feasibility of its implementation. It is not the ethics of divestment that causes concern; rather, the practical aspects of this process of divestment are what gives pause to small, often under-resourced organisations. Divestment can seem like a massive commitment; a project that will consume time and knowledge that is, most often, not available. In contrast, the promise of the cloud is one of sleekness, ease of use, and practicality; indeed, Big Tech companies invest vast sums of money in the design of frictionless user experiences. Over the past years, this drive towards frictionless experiences has led to a distinct depletion in important skills, fostering a sense of helplessness. It is precisely this sense of helplessness that maintains individuals, communities, and organisations tethered to harmful processes, technologies, and systems—the spell that keeps us wandering in this house of mirrors, uncertain of what is real and what isn’t, unaware that we are, in fact, not alone, and not helpless.

The Regime of the Cloud

The Regime of the Cloud is a techno-social amalgamate of tools, infrastructures, devices and modes of doing that produces harm to all forms of life. It can be understood as both a technical architecture and a political-economic apparatus, designed to preserve colonial order by shaping contemporary conceptions of value, labor, visibility, and control.

In concrete terms, divesting from the Cloud might mean finding ways to avoid using Google maps, replacing Zoom by Jitsi, disengaging from Meta's Instagram, or switching from WhatsApp to Signal. However, the practice of divestment demands a much deeper interrogation of the ways in which we work, how we relate to each other, how we organise individually and collectively, how we manage time, and how we engage with our surrounding environment. As daily life becomes punctuated by the constant, persistent presence of the smartphone, our habits and expectations—of ourselves, of each other, of our communities and societies—are rearranged and reconfigured. Everyone is a social media manager and content creator; we are all brands, we all work for the tech oligarchy.

Operating in a centralised yet globally distributed logic, the Regime of the Cloud establishes these distinctive modes of governance, enforced across multiple dimensions of contemporary life and encompassing technical, economic, affective, and ecological milieus. The Cloud becomes a repository of the signifiers of the contemporary human condition; a techno-social amalgamate capable of converting our bodies, our affects, our identities into data, ready to be commodified. These modes of governance don’t merely structure and regulate behaviour; rather, they reconfigure how subjects, infrastructures, and territories are organised, made visible, and acted upon.

A Spell for Spellbreaking

Breaking the spell begins with refusal.

Breaking the spell begins with experimentation.

Breaking the spell begins with playfulness.

Spellbreaking invites us to step away from the shadow of the Cloud. Lean into the sunshine.

Spellbreaking invites us to challenge, subvert, and corrupt the conceptions of time, abundance, productivity, and relevance that we find in the shadow of the Cloud.

Spellbreaking invites us to refuse linear, arrow-like trajectories; let the uncertain terrain of the wild web guide your steps through meandering paths.

Spellbreaking rejects ideas of perfection and purity; the spellbreaker knows that no technology is halal.

Spellbreaking does not long for an idealised past, but rather summons futures anew.

Spellbreak training manual

As related above, loneliness and isolation is the first spell to break. This training is therefore based on a networked practice of inter-organisation coaching, using each others' capacities and pockets of availability to create confidence and capacity for transformation. The training starts by one organisation calling for help at another. Together they find time to spend one to two days together without too many external demands or tasks, in order to do this work. Before physically meeting, the process starts by answering a number of intake questions that ideally could be discussed with all the stakeholders at the organisation — for example, their board and organising committee. The responses to the questions will be useful at this point in the process because they reveal specific concerns and patterns. By involving different people in the organisation in the process, both the trainee and their colleagues are reminded that they cannot do this work alone; rather, the training is an invitation to imagine alternative ways of operating can offer a productive pathway to how to establish liberatory practices across the various dimensions of an organisation.

When first contacting TITiPI, Ailie suggested working together to look at how Market Gallery could move all aspects of their working processes—including digital tools and communications—to more closely align with the progressive, anti-genocide, feminist, anti-colonial positions of Market gallery’s exhibition and events program, as well as the political intentions of the organisation. In order to investigate this further and prepare for our upcoming meeting, we sent a series of questions for Ailie to present to their peers at the Gallery. These were meant to help us take stock of Market Gallery’s current situation, and to understand what were the main concerns, limitations, fears, desires, and visions of its staff, committee, and board members. When presented with this set of questions, the Gallery’s committee expressed significant fears when confronted with Ailie’s proposal to concretely divest from the Cloud; and a concern that divestment from tools like Google Drive or Gmail would lead to a collapse of the workflow at the gallery. In many ways, the questions offer both a starting point, and a reference that we can go back to as the divestment process unfolds; they are a way to align priorities, and propel conversations.

Here are the questions:

1. What is the current relationship that your organisation has with cloud infrastructures in the context of your organisation?

2. What have you observed in terms of the relationship of your organisation to these infrastructures? Are there any obstacles or particular conditions or contexts that we should be aware of?

3. In your view, what kind of impact could the knowledge generated through this process have for colleague organisations?

4. What would you like the result of this process where we critically engage with cloud infrastructures to be? How do you formulate your vision?

5. What do you think could be a first step towards this process, in the context of the practice of your organisation?

6. Would you be open to connecting with another local organisation in this process, so that we could develop this framework together?

Try answer these questions before consulting the sample answers below. Afterwards, look for patterns and differences.

→ Sample answers Market Gallery board

→ Sample answers Market Gallery committee

On Skills and Collectivity

Spellbreaking work is meant to be collective as well as trans-generational; after all, divestment requires us to be able to develop and establish new labour infrastructures as well as the ability to develop new ways of communicating and disseminating work amongst the wider public. Additionally, the staff in a small organisation will almost certainly lack the full spectrum of skills, knowledges, technologies, and infrastructures needed to divest from the Cloud; it is not every organisation that has the time and financial and technical resources to set up their own server for file storage, for instance. In order to address this issue, it is then fundamental that we understand that spellbreaking needs to happen as a collective articulation; this means establishing an ecology of organisations, individuals, and other agents who are willing to support each other in this process. The house of mirrors built by Big Tech prevents us from fully grappling with the fact that, when acting collectively, we are not helpless. Spellbreaking means, too, learning to ask for help when necessary, and offering help when capable.

Whilst full divestment is a desirable outcome, it is also important to understand that this might not be immediately achievable, and might not mean the same thing for everyone involved in this process. An organisation can have a certain level of control over its own internal processes, and how it chooses to communicate with the public. However, they might be required to engage with the Cloud when interacting with external agents—for instance, when a grant form makes use of Google or AWS products and services, or when social media metrics becomes a key factor for the success of an application. These are significant limitations to full divestment, but it is important that they are not perceived as a complete impediment to undertaking this experiment. It is also important to note that not every agent involved in this collective process of divestment might be able to enact it in the same way or in the same rhythm. Some might be able to take their spellbreaking experiments further than others; once again, this must not be seen as an impediment, but rather as an opportunity to observe and understand the limitations and questions that surround the process of divestment.

Collectively negotiating the complexities of our engagements with the Cloud must, therefore, also constitute a fundamental aspect of spellbreaking. What would happen is not one, but multiple organisations, individuals, and other stakeholders demanded that funding agencies also divest Regime of Cloud, opting instead for other modes of storing and exchanging information? What would those alternative modes of sharing and exchange look like? What would it mean to understand that the avenues for the storage and exchange of key information, as well as the communication and dissemination of knowledge, culture, and art are not something that can be left in the hands of Big Tech companies, but rather something that needs to belong to the commons? What would those commons look like?

A variety of skills will be needed to address these questions. This small and non-exhaustive list offers a suggestion of the various agents that might be involved in the process of spellbreaking:

- Individuals and organisations able to set up and offer alternative structures and platforms for file storage and exchange;

- Individuals and organisations able to develop and implement effective communication strategies with the public that circumvent the pervasiveness of social media;

- Individuals and organisations able to establish effective community-building programmes, fostering encounters, synergies and connections at both local and extra-local levels;

- Individuals and organisations able to set up and offer alternative modes of internal/external workflow-related communication (email, instant messaging);

- Individuals and organisations able to operate on the policy level, with the intent to propose shifts in modes of working and communicating to both governmental and non-governmental funding agencies, regulatory bodies, and other stakeholders.

During the time we spent together working on this spellbreaking proposal, Ailie suggested an experiment: navigating the city of Brussels, where Titipi is located, without relying on Google Maps. Luiza, who also does not live in Brussels, decided to join the experiment. One of the most immediate and visible results was the establishment of a fundamentally different relationship with public space; not using Google Maps, we had to instead rely on tools like paper maps, Open Street Maps, public signage, the city’s own travel planning system, as well as simply asking strangers for directions. This allowed us to observe how information on transport and navigation—fundamental public services in any urban space—were lacking in Brussels. Bi-lingual signage was confusing, particularly when navigating the city’s cryptic transport system. Open Street Maps offered an alternative, but lacked the precision we are used to in terms of GPS location; therefore, when using it, we often had to observe our surroundings much more attentively. Asking for directions from strangers offered, perhaps, some of the most interesting dimensions of this experiment; for instance, the surprise expressed by the cashier at a small family-run food store when Luiza asked for directions on how to walk to a relatively distant park to meet Ailie and Femke. The cashier was struck by both Luiza’s insistence to walk, and the refusal to use Google Maps. The cashier knew it was a relatively straightforward path, but wasn’t absolutely sure. She asked a colleague to explain directions, who said he also wasn’t sure. Ultimately, she ended up looking for the directions on her own phone, on Google Maps. The idiosyncrasies of this experiment also became evident in other moments—for instance, when Femke and Ailie used a phone as a lighting device to be able to see a paper map in the dark.

Portals and Wayfinding

Over the course of our experience in Brussels, it became increasingly clear that the path towards divestment was not at all linear. In this sense, it was perhaps the No Google Navigation Experiment that offered the most poignant blueprint of the meandering nature of divestment: a process that demanded the involvement of multiple actors, encroached by less than ideal circumstances, inherently imperfect, yet capable of offering unpredictable or surprising results that brought about new understandings of our relationships to each other, and to the spaces through which we circulate. In rejecting a private company—Google—as a mediator to our relationship to public space, we were able to observe with a more keen eye both the strengths and fragilities of other wayfinding technologies and strategies across multiple spheres of an urban commons.

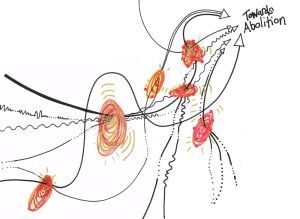

Divesting from the cloud is not a frictionless journey—rather, it unfolds through moments of convergence, possibility, and choice in a process of collective wayfinding. We understood these moments of convergence as portals: openings that revealed, even if just for a brief moment, a different configuration of tools, desires, and relationships. Moments that pointed toward new, imperfect pathways. Some portals could be more straightforward or obvious than others—something as concrete as switching from Gmail to a locally hosted service. Some could be more abstract, such as the collective realisation that attention is a finite but shared resource that is not inherently tethered to the Regime of the Cloud.

Each portal invites us to redirect our meandering paths, to step away from the logics of extraction and toward other forms of presence rooted in solidarity, interdependence, and experimentation. Stepping through these portals, however, demands caution. A portal is not neutral, nor inherently liberatory; if approached as a mere technological transition rather than as an opportunity for decolonial, transfeminist, and anticapistalist praxis, a portal can replicate and perpetuate the same harmful patterns of exclusion and control. Here is where collective action also assists us in establishing mechanisms of accountability for spellbreaking.

Wayfinding through portals is rarely done alone. Instead, this is a collective movement, a shared process where organisations accompany one another through uncertain terrain—a process that can play a dual role, facilitating both change and accountability. Granted, not everyone will step through the same portals at the same time—or in the same way. Some may sprint ahead, others may hesitate. Some may be able to implement structural change quickly, while others must move slowly, negotiating their own specific contradictions and constraints. The imperfection of the spellbreaking process is not a deterrent; rather, it needs to be understood as a feature that reminds us of the need to constantly assess and re-evaluate the direction we choose to take—with the understanding that this might, at times, approximate one actor to another, and in other times result in divergent paths. This asymmetry is not a failure—it is inherent to the ecology of collective divestment.

In this context, gatherings—ritual, joyful, mundane—can become points where concurrent processes of orientation, reorientation, and disorientation take place. What would it mean to throw a party where attendants can leave Instagram together as a way to collectively soothe the insecurities that come with the divestment from a platform that promises exposure, attention, and connection but is ultimately implicated in systems that harm all forms of life? What kinds of insights could we gather on the meaning of attention, exposure and connection, and what alternative forms of operating could we conceive, stemming from those new formulations?

The party as portal can be a moment of rupture, but also of flourishing; it offers glimpses of another form of presence, other conditions to life. The party exists solely for the purpose of delighting in each other's presence—a counter-action to capitalist utilitarianism. The act of stepping through this portal is not about the arrival, but about the movement itself. It is the creation of a choreography of care, with the knowledge that spellbreaking is not about purity or perfection—it is about choosing, again and again, to reconfigure our participation in extractive systems, and doing so collectively. These acts resist the narrative that divestment is only loss; they open, rather, toward a vision of abundance: of imagination, of care, of alternative ways of being together.

The Oracle and the Cloud

Other forms of thinking, feeling, and being together might also be useful in these processes of orientation, reorientation, and disorientation.

During our two-day workshop in Brussels we held a divination session, using a tarot deck, to help us triangulate thoughts and reflections on what divestment could mean in the context Ailie was working from, and the specificities and constraints that characterised Market Gallery and FEN. Luiza asked Ailie to think of a question as she shuffled the deck. Ailie then chose three cards, which we positioned in sequence. We used the first card as a lens to examine the past events that established the foundational context for Ailie’s question. The second card was meant to aid us in reading the present conditions under which we were operating. The third card was meant to offer advice on how to move forward, and imagine what other possibilities lie ahead. During the divination session, it is important that whoever is acting as the reader makes use of the full spectrum of their senses as they seek answers: observe the cards, their message, the elements in the image they display. Take in the smells, the light, and the sounds in the space you are in, noting if, how, and when they change. Take stock of your own emotional state, and that of the others involved in this process. Card reading is a deeply intuitive process that encourages us to understand and situate our condition as subjects embedded in the intricate, beautiful web of life, much bigger and more complex than ourselves.

Sample portals

- Moving to Mastodon

- Moving file storage to Nextcloud

- Find another way to think with availability

- A conversation about arguments, paradoxes, contradictions and complicity

- A (creative) statement of some sort

- Connect with a partner organisation to discuss, try out, document the process of stepping out of Instagram, Google or Microsoft teams

- Setting up an oblique strategies tarot session

- Throwing a party to leave social media together

- Establishing other foms of staying in touch and building community: regular meetings, dinners, reading groups, etc.

Sample schedule

The spellbreak training takes ideally place in a location away from the trainee's daily environment. The hosting organisation should take care to provide time keeping, basic necessities such as a comfortable place to work, food, coffee, fruits etc.). The below schedule is a suggestion but can be adjusted according to the specific needs of the involved organisations.

Day 1

10:00 Coffee and hello

10:15 Intake: collective analysis of questions and answers

11:15 Divination I

12:15 Break

12:30 Infra-tour of the hosting organisation

13:15 Excursion to meet an allied local organisation, picknick

16:00 Consultation: Tactics, approaches, where to start?

17:00 End

19:00 Drinks + dinner

Day 2

10:00 Reading outside (if possible in a garden or park)

11:30 Divination II

12:30 Lunch

14:00 Concrete intervention

16:00 Break

16:30 Portals: planning and further steps

17:00 End of training!

Resources

Why breaking the spell

- On digital ethics for cultural organisations https://cloud.encc.eu/s/dXYWA7LN95dtDgn

- Dear student, teacher, worker in an educational institution, https://constantvzw.org/wefts/distant-elephant.en.html

- Trans*Feminist Counter Cloud Action FAQ https://titipi.org/pub/FAQ.pdf

- Defund Big Tech, Refund Community. Anti-Trust is Not Enough, Another Tech is Possible https://techotherwise.pubpub.org/pub/dakcci1r/release/3

- Counter Cloud Action Plan https://titipi.org/pub/Counter_Cloud_Action_Plan.pdf

- Boycott tech/pressure targets BDS https://bdsmovement.net/sites/default/files/styles/media_block_m/public/2025-01/2.png

- The rise of end times fascism https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2025/apr/13/end-times-fascism-far-right-trump-musk

Related spellbreaking

- Degooglify the Internet (Let's get out of Google): https://degooglisons-internet.org/en/

- Escape-X: https://www.escape-x.org/

- Vamanosjuntas (Let's go together): https://vamonosjuntas.org/

- Regime change: a day long session, aimed at aligning the computing infrastructure of a cultural organisation with the ambitions and aspirations summoned by the commons (proposed by Kate Rich, Femke Snelting and Magdalena Tyzlik-Carver) https://www.constantvzw.org/site/Regime-Change,2673.html

- Welcome to the Fediverse: guide to a different approach to social media https://titipi.org/wiki/index.php/File:Welcome_to_the_fediverse.pdf

- https://www.tacticasbl.be/agenda/desintox-numerique-quelles-solutions-face-aux-ingerences-politiques-sur-les-reseaux-sociaux-2/

- Community calendar in NYC to get outside of Meta infrastructure https://cal.red/?event=about

- Infra-resistance booklet https://titipi.org/wiki/index.php/RESISTANT_INFRA

- Varia Mastodon https://varia.zone/en/social-in-the-media-get-together.html

- https://alternatives-in.uk/to/

- Slow-it: for a slower, more modest mode of computing https://slow-it.be/

- Permacomputing wiki https://permacomputing.net/

Divination

- Bewitching Technologies: https://bewitchingtechnologies.link/

- Tangible Cloud Oracle: https://bleu255.com/~marloes/projects/Tangible_Cloud_Oracle/

- Splint cards: https://calibre.constantvzw.org/book/182

- The oracle for transfeminist technologies: https://transfeministech.codingrights.org/

- Oblique strategies: https://obliquestrategies.ca/

Examples

- Beursschouwburg, a theatre and cultural organisation in Brussels, has recently decided to phase out their use of Instagram. In this article they explain why they took this decision and how they gradually are divesting attention from Meta's platform: https://www.bruzz.be/actua/cultuurnieuws/cultuurhuizen-experimenteren-met-alternatieve-sociale-mediaplatformen-tegenstem

- Constant, association for art and media has a long history of making technological experiments part of their artistic program. In this essay one of its members describes the association's particular practice with the online collaboration tool etherpad https://march.international/constant-padology/

- The activist research collective TITiPI experiments with digital infrastructures that do not centralise nor converge. Not meant as a how-to guide, their thinking through what it means to approach e-mail services otherwise can be interesting to reflect with: https://titipi.org/wiki/index.php/None_of_this_experiment_is_evident

- Varia, a collective for everyday technologies makes a point out of listing each and every technology (social and digital) on their website. Together, these tools form a portrait of the organisation: https://varia.zone/en/pages/collective-infrastructures.html

- Two artschools in Brussels (ecole de recherche graphique and La Cambre) collaborated to divest from Google, Zoom and Microsoft in education. Their experiences are helpful to understand what can be gained, how such a process is started, and why it is important to step through such processes in collaboration: https://gsara.tv/teletravailler/erg-libre/

Other

- https://computingwithinlimits.org/2021/papers/limits21-devalk.pdf

- https://archives.tangible-cloud.be/207_from-appropriate-technology/

- https://titipi.org/pub/Infrables.pdf

Colophon

The Spellbreaking manual was written on the basis of a two day session at the TITiPI collective garden in Brussels, May 2025. Thank you Ailie Rutherford for joining us, Gwendolin Barnard and Constant (Imane Benyecif) for your generous contributions, Dilan U+16DE for Bewitching Technologies. Spellbreak training follows from the Counter Cloud Action Plan (with NEoN, Dundee). The training is an activity in the TITiPI Community Research track, developed as part of the CHANSE funded project SoLixG (with Helen V Pritchard). Text written by Luiza Prado feat. Femke Snelting, laid-out with the help of wiki-2-pdf by Luiza. This manual is committed to a collective practice of reuse. For more, see: cc2r

Download this guide at: https://titipi.org/pub/Spellbreak_training.pdf

Plain text version: https://titipi.org/wiki/index.php/Spellbreak_training