Unfolding:Tactileanalysis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<div class="pagebreak"></div> | <div class="pagebreak"></div> | ||

<div class="pagebreak"></div> | <div class="pagebreak"></div> | ||

{{TT|Introduction}} | |||

{{TT|How_to_feel_things}} | {{TT|How_to_feel_things}} | ||

{{TT|Co-habitations}} | {{TT|Co-habitations}} | ||

Revision as of 11:44, 10 May 2023

Tactile Analysis

Infrastructural Interactions: Survival, Resistance and Radical Care

Cristina: Even if the infrastructure fails, there's all this imagery around it that connects to progress, ideas of progress, and ideas of modernity and that has a lot of rhetorical power. I think thinking about other ways politics or other ways of interacting with, of building an image around infrastructures is really valuable, actually. At least, for me, the most convincing that I've encountered, I don't know.

Clareese: Definitely, yes. I do agree too. Infrastructure or the idea that it's not going away, so how do you use it and make it useful to the people that it's supposed to act as a container or a boundary around?

Radical Care

As public health care nearly collapsed under pandemic pressure, schools closed and movement through public life became increasingly monitored and managed by digital infrastructures, we have been thinking with other collectives about radical alternatives to the need for care. For the last two decades, basic care provisions have been turned into tools that perform racial capitalism, excluding and punishing those who needed it most. What kind of solidarity and support can people extend and receive to one another that is outside the scope of the limits that are being imposed on us, from the voluntary duty of care to not expose one another, to a state supported obligation to function as a subject to capitalism? The fact that the pandemic made it impossible to come together physically to organise and to resist, triggered many discussions and reflections. When lockdowns immobilised a lot of the practical options that common people and ordinary working-class people have for resistance, which would be their bodies and the street, or meeting to make plans or to provide care for each other, cloud infrastructure has often been presented as the way forward — such as hosting organising over Zoom, using Google Drive to distribute materials or Uber to distribute care packages.

For the conversations and workshops that feature in this manual, we brought together people involved in alternative healthcare or other alternative care-structures, for example in the context of anti-fascist activism, or groups rethinking alternative technical infrastructures in terms of capacity and care. Without wanting to turn everything into infrastructure, we felt it was helpful to open up perspectives that point out the worlding qualities of caretaking, maintenance and instituting.

From survival to resistance in racial capitalism

As people who are active on the ground, but also intellectually, what do we imagine in terms of resisting and building alternatives for or to cloud infrastructures? What are our lived experiences with infrastructures that demand these alternatives? A question that came up often in our discussions and practices was whether this is a time of survival, or a time of resistance? Are the creative imaginaries we are exchanging, an example of resistance ... or are they actually about just surviving? We were interested in asking this question, because we know that people are sometimes using extractive services and apps, knowing very well that it's a risk, and that by using them, they're actually being exploited even more.

In the workshops, conversations and collective writing that generated this workbook, we have tried to think resistance under racial capitalism and issues around extractivism with participants from different geographies and practices. What are the material aspects of cloud infrastructures that are being imposed on us, during COVID-19 lockdowns and since? It felt these questions where erased from the debate, even among critical scholars working on technology, while obviously racial capitalism and extractivism are part of the conversation. This workbook brings attention to the ways in which computational infrastructures extend extractivism, from the mining of rare minerals for smart phones to the extractivist models of cloud-based services and the extension of Big Tech into the markets of care. To do so, we build on a body of literature pointing out the continuing geopolitical make-up of imperial and colonial power in the development of infrastructural technologies. In particular, Syed Mustafa Ali argues for a decolonial approach when designing, building or theorizing about computing phenomena and an ethics that especially decentres Eurocentric universals.[1] Paula Chakravartty and Mara Mills offer to think decolonial computing through the lens of racial capitalism.[2] Cedric Robinson argues that mainstream political economy studies of capitalism do not account for the racial character of capitalism or the evolution of capitalism to produce a modern world system dependent on slavery, violence, imperialism and genocide.[3] Capitalism is ‘racial’ in the very fabric of its system.[4]

The work documented in this workbook is embedded in a view that requires continuous undoing – a necessary but unfinished formal dismantling of colonial structures by decolonial resistance. Building on theories of racial capitalism, we focus on the implications of computational infrastructures and their relation with extraction, whilst working on ways to develop a non-extractive research practice.

What does Cloud infrastructure do?

Cloud infrastructures purposefully promote data intensive services running on the infrastructures, rather than pre-packaged and locally run software instances. These data-infrastructures range from health databases, border informatics, data storage warehouses, to city-dashboards for monitoring citizen flows, educational platforms and the optimisation of logistics. It has become common for theorists, activists, artists, designers and engineers that want to critique cloud services, to focus on the way they extract data from individuals, either for value or surveillance, or to automate services so that institutions can reduce workers rights or employ less people. The research we are doing at TITiPi however evidences quite clearly that this might not be the best way to understand what clouds are and how to resist and prepare for the massive shifts in public life they are and plan to make.

Instead, we propose that what we need to look at how Big Tech cloud services are financialising literally everything on a rentable model, thereby indebting institutions, communities and individuals to their values and services. Cloud infrastructures offer agile computational infrastructure to administer, organise and make institutional operations possible, decreasing the potential for institutions to manage their own operations, locking them into a cycle of monthly payable subscription agreements (debts) and rendering all operations from emptying bins, to paying bills, to hosting collaborative documents ready to be financialised by Big Tech cloud companies. They do this by promising a future of being able to fullfill the operations that institutions themselves might not even have imagined. By interfacing between institutions and their constituents through Software-as-a-Service solutions, they reconfigure the mandate of institutions and narrow their modes of functioning to forms of logistics and optimization.

As Big Tech extends into public fields, they tie together services across domains, creating extensive computational infrastructures that reshape public institutions. So the question is, how can we attend to these shifts collectively in order to demand public data infrastructures that can act in the "public interest"? And how can we institute this? Computational infrastructures generate harms and damage beyond ethical issues of privacy, ownership and confidentiality. They displace agencies, funds and knowledge into apps and services and thereby slowly but surely contribute to the depletion of resources for public life. While data- infrastructures capture public data-streams, they also capture imagination for what a public is, and what is in its interest. We urgently need other imaginations for how we interface with infrastructures, beyond delivering a “solution” to a “need” (or the promise they can fulfill a future need).

The workshops, documentation and structures in this workbook are a small contribution to making this complex paradigm shift together.

How to feel things?

We feel through the senses. When we are sensing, we generate different types of information: tactile, visual, auditory, gustatory, olfactory. We feel the texture of an object, we perceive the qualities of its surface, an image of its contour, an idea of its material, an imagined colour. We compose these sources of information into experience.

One is waken up by the increasing sound of the bird song fading in into our sleeping unconscious. The texture of the sheets enters our awareness via our skin, we are reminded we are in bed. The smell of rain, its drizzle sound. The morning light filters into the eyes. One judges by its quality and intensity, if this is a cloudy morning. Proprioception or kinaesthesia is the sense of self-movement, force and body position.[5] We know we are in bed, we feel our body is in an horizontal position. Our muscular system recalibrates while we feel the need of stretching. Our eyes gain sharper focus.

A sensing experience can transport us to the realm of memory: we feel the present, the past and the future too. Depending on our personal memory, the experience of a rainy morning may bring up hopeful feelings of a pulsing Spring, or the cold sadness of grey days. We feel with the gut and the heart too, we create visceral information. Our nervous system extends through the intricate territories of our biological suit and collects data, which is later translated into different languages and layers of experience.

We feel and sense at the same time. Sensing is organised into a complex experience which we call feeling. A "feeling" could be described as the intensified meta experience of juxtaposed sensing information. We learn and connect with the world through sense and feeling. If one ponders on the question on how to feel things, one may land at a subsequent question: How to know things? How is that we create knowledge about things at all? In much of the world influenced by the western gaze, there is an stablished hierarchy dictating which sensing information is privileged and which is discarded in the process of knowledge creation. We tend to privilege visual and auditory information over tactile and visceral sources. Reconsidering and dismantling these epistemological[6] hierarchical structures demands from us to embody our full senses: to drive focused attention and open gates to the intricate details of the sensing information we are receiving in its fullness, before our judgement discards it.

How can we approach the textural without giving primacy to our Western knowledge-eye? How can we stop "seeing" as both a visual act and a way of knowing, an open ourselves to feeling as an act brimming with knowledge, affect, and social and individual memory? [7]

Stay for another dance

It is said that co-habitation is the fact of living or existing at the same time or in the same place. In a more orderly-establishment sense of the word, it is reduced to refer to a personal and even sexual relationship with another human that lives and exists at the same time or in the same place with you. Both definitions feel short, maybe too short, for what the experience of co-habiting entangles and opens.What makes co-habitation possible is –What is it what enables co-habitation? Can we co-habit in different timelines or at multiple places? How do we experience and recognize our co-habitation with other living and dying organisms which are not human?

you want to find out what happens next – this common wish creates the conditions for the situation, one that tells a story you are becoming with.

So the fact of living or existing, assisting and insisting in certain time and place, together and maybe publicly with others, not only human but critters, objects and invisible presences, is the fact that creates the surface to tell a story, an extended mat where you dance. Here your dancing moves keep growing out of the last movement. And these moves –elliptical distracted repetitive sensational – are all inevitable invitations for you to recollect and tell the stories you are moving with. Because your body is moving and feeling and breathing your surroundings, it has the capacity to hold and channel multiple layers of time, an array of places, and numerous material vibrations, to tell your co-habitation stories.

To do so, you can build the story as your house[8], or refuge – as literal as it is, because we are talking about our ways of inhabiting and who or what doesn't enjoy a nest. A house or refuge is something to come into from the outside, so maybe you want to have a welcoming entrance, to have an open front door that shows a glimpse of what is inside.

Once in, different and various things can happen, entangled paths, big and small rooms, up and down stairs, windows, garden pockets, an attic, warm corners, death alleys. Your guests might live there for a short or long while, you can choose to show them the view, cook something, have a nap in the hall. Somehow it seems important to have a back door, because you want to know what the back door opens onto, a way out to go, maybe to the house next door, maybe to pick up the dancing in the playground.

G3n7l3 N01s3

0r1g1n

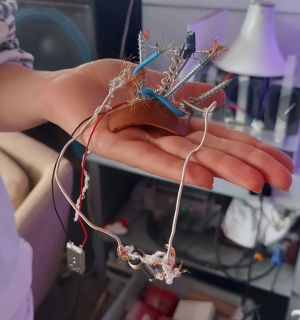

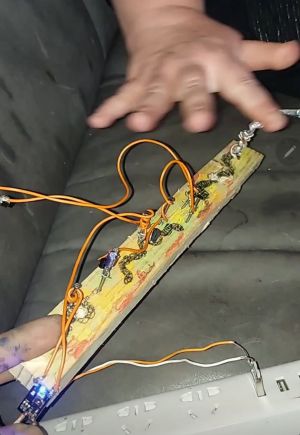

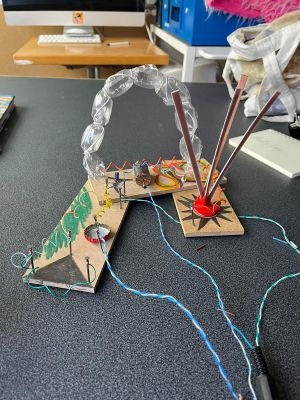

Noisey craftmanship and colorful additions combined with vibrating hamburgers, mothers and hotdogs invite you to release the gentle noise. You can shape the noise by light and touch, using your fingery-ears.

The gentle noise project is spreading the idea of transforming what is considered waste into gentle noise. It started in Thailand as a part of funeral ceremonies using DIY audio technology. The artisanal approach is carried on in the project. Not only the sound but the means are unique to its creator.

About อาจารย์* Arnont

Arnont Nongyao lives in Chiangmai (TH) - Ho Chi Minh city (VN) and He is an artist interested and fell in love with the vibration of things. He likes listening to everything that inspires him to do experimental sound art. The most important teacher “the master Khvay Loeung "inspired him to listen and “destroy yourself from being yourself”[9]

A message from อาจารย์* Arnont:

.-.. .. ... - . -. -.-- --- ..- .-. ... . .-.. ..-.

A message from the synthesizers:

- .... .- -. -.- ... ..-. --- .-. - .... . ..-. ..- -.

- read: Ajahn, meaning Salutation for Teachers in Thai

a little story on generating gentle noise

It's a Tuesday afternoon in the HacketeriaLab in Zurich where 8 12 Volt Amusement Parks are being played. They all come in different shapes and sizes but tell a similar story.

It's a day full of scraps, connections, food and noise inbetween hammering, laughter and sharing concerns and apologies.

After a small removal of its third wire, a Kid gets to take a piggyback ride on its mom's shoulders.

The hopping and bending make them hungry and luckily there are a few options. The mom gets a positively charged hotdog with ketchup, mustard and black sesame seed mayo. Its a special Tuesday so the Kid gets chose what it wants to eat. First it choses to eat a pancake but soon enough realizes he needs more energy for the next ride. He goes with a negatively charged, hand flipped hamburger.

After a little rest they take the famous Jack Speaker Rollercoaster. The Sun comes out from behind the Clouds as it provides for positive vibrations and you hear children screaming as they're thrown up and down.

- ↑ Ali, S. M. (2016), ‘A brief introduction to decolonial computing’, XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students, 22:4, pp. 6–21.

- ↑ Chakravartty, P. and Mills, M. (2018), ‘Virtual roundtable on decolonial computing’, Catalyst, 4:2, p. 14

- ↑ Robinson, C. ([1983] 2000), Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, G. (2018), Rethinking Racial Capitalism: Questions of Reproduction and Survival, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proprioception

- ↑ "Epistemology is the theory of knowledge. It is concerned with the mind's relation to reality. What is it for this relation to be one of knowledge? Do we know things? And if we do, how and when do we know things?"https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/philosophy/research/themes/epistemology#:~:text=Epistemology

- ↑ Patricia Alvarez Astacio. Tactile Analytics. Touching as a Collective Act. p. 17

- ↑ ** While writing this text I borrowed some dance moves from Ursula K. LeGuin, a good friend.

- ↑ http://www.arnontnongyao.com/about.html