SoLiXG:Home: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | {{solixg}} | ||

== The Social Life of XG: key concepts == | |||

<!-- with changes in javascript and css this page was edited --> | |||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

<div style="display:none;"> | <div style="display:none;"> | ||

{{:SoLiXG:Key-concepts}} | |||

</div> | |||

< | <!-- | ||

<DynamicPageList> | |||

namespace=SoLiXG | |||

category=keyword | |||

mode=none | |||

shownamespace=false | |||

ordermethod=sortkey | |||

order=ascending | |||

</DynamicPageList> | |||

--> | |||

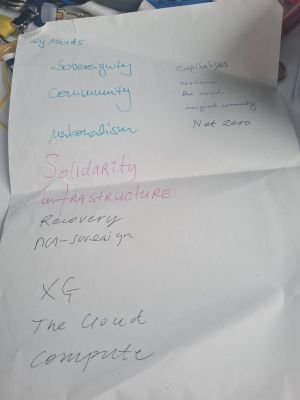

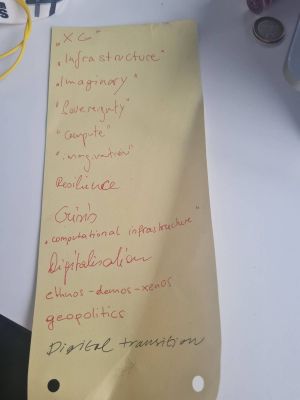

[[File:Signal-2023-03-14-103500 002.jpg|frameless]] [[File:Signal-2023-03-14-103504 002.jpg|frameless]] | |||

------ | |||

Latest revision as of 11:09, 5 September 2023

The Social Life of XG: key concepts

Contents

- 1 The Social Life of XG: key concepts

- 2 PUBLISHED ON SOLIXG WEBSITE

- 3 Automation

- 4 Bordering

- 5 Cloud infrastructure

- 6 Compute

- 7 Crisis

- 8 Twin transition

- 9 Digital Infrastructure

- 10 Digital Non-Sovereignty

- 11 (Digital) Sovereignty

- 12 Imagined community

- 13 Resilience

- 14 Stack

- 15 Technological Solutionism

- 16 The crowd

- 17 The Social Life

- 18 The Social Life (Reworked)

- 19 The State

- 20 XG

- 21 SELECTED

- 22 Imaginary

- 23 Imagination

- 24 Reconfiguration

- 25 Ideology

- 26 Progress

- 27 Nationalism

- 28 Standardization

- 29 WAITING ROOM

- 30 Acceleration

- 31 Community/commons

- 32 Digital boundaries/borders

- 33 Digital Capitalism/Techno Capitalism

- 34 Digital transformation

- 35 Ethnos, Demos, Xenos

- 36 Geopolitics

- 37 Net-zero

- 38 Digital Currency

- 39 MERGED

- 40 Infrastructure

PUBLISHED ON SOLIXG WEBSITE

Automation

The concept of automation denotes a broad range of processes. It can be understood as a synonym of technical development in general: the process through which techniques and methods of production, distribution, and communication are “rationalized”, or rendered more “efficient”, so as to become increasingly “independent” of human labor.

Today, the term is perhaps most often used in discussions of “digitization”, the development of “smart” systems of different kinds, and AI. Understood in a general sense, however, a full history of automation would need to include all phases of technical and industrial rationalization, from the mechanization of manual labor during the first industrial revolution, to the robotization of intellectual or cognitive labor in the present.

The word comes from ancient Greek (automatos, self-acting), but the specific inflection “automation” – a verbal noun – is relatively recent: it was first used in the postwar cybernetic discourse in the US, to describe the development of feedback-operated, self-correcting and self-managing technical systems. (1) “Automation” has retained some of the techno-utopian connotations of this historical moment. New generations of automated or “intelligent” machines are routinely marketed as the outcomes of a linear and self-sufficient process of technical evolution. (2)

Critical studies of the history of automation have shown that it must instead be understood as a fundamentally social and conflicted process. The protocols of modern, industrial automation, as David Noble has detailed, were derived from the patterns of behavior, and the logics expressed, in collective labor processes. (3) Similarly, the data sets and the algorithms that make up the “inner code of AI”, as Matteo Pasquinelli has recently argued, are “constituted not by the imitation of biological intelligence but the intelligence of labor and social relations”. (4)

In this respect, “automation” has been and remains a necessarily ambiguous term, the differing implications of which outline a basic political opposition. Understood as the driving principle of the rationalization of methods of production within the framework of intra-capitalist competition, automation will inevitably run counter to the interests of workers, who risk facing inhuman labor conditions or unemployment. (5) (Automation is inevitable, as a General Electric executive is reported to have said in the 1950s, but “it takes a lot of hard work and sacrifice by a lot of people to bring about the inevitable”. [6])

On the other hand, automation also harbors a progressive, liberating promise: the promise of a world without degrading work, of an existence with more free time, leisure, even – in a romantic, utopian spirit – of a life that can be realized in its fullness as free play. More modest versions of such demands have been central to the modern labor movement, and are continuously being updated by new generations of workers, activists, and thinkers. (7) More utopian post-work imaginaries, meanwhile, have generally been the prerogative of avant-garde movements (think of the Situationist International’s “Never Work”). Common to automation’s progressive promises is that they are in contradiction with the continued existence of capitalist relations of production.

(1) Friedrich Pollock, Automation: A Study of its Economic and Social Consequences (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1957), p. 3.

(2) See e.g. Pedro Domingos, The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World (London: Penguin, 2017).

(3) David F. Noble, Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2011), p. 324f.

(4) Matteo Pasquinelli, The Eye of the Master: A Social History of Artificial Intelligence (London: Verso, 2023), p. 2.

(5) For a report that acknowledges this conundrum, but provides an optimistic path forward, see The Changing Nature of Work: 2019 World Development Report (Washington, D.C.: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, 2019).

(6) Quoted in Noble, Forces of Production, p. 230.

(7) See e.g. Nick Srnicek & Alex Williams, Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (London: Verso, 2015), Ursula Huws, Reinventing the Welfare State: Digital Platforms and Public Policies (London: Pluto Press, 2020), and James Muldoon, Platform Capitalism: How to Reclaim our Digital Future from Big Tech (London: Pluto Press, 2022).

Comment (A): I think it is very clear and nicely written. Would leave it as it is.

Bordering

Bordering emphasizes the production and re-production of borders. Although semantically concerned with territoriality, which draws the line of an exclusive space, not seldom the sovereign nation-states’ territory,[1] theoretical conceptualisations of borders tend to focus on technologies of inclusion and exclusion, and of state and corporate violence and discrimination. As Mbembe argues, borders are mere lines separating distinct sovereign entities but rather a term we should deploy for today’s organised violence that underpins ‘both contemporary capitalism and our world order in generally.’[2] Because borders are performative, polysemic and heterogeneous,[3] we can study them as practices.

Border practices or bordering find new modes of operation when challenged and threatened to become porous. In many theoretical accounts in migration studies, borders and bordering are allocated to several levels of state power in cooperation with private actors hampering and endangering people’s movement. The porosity of the border has given rise to a logistification of the border regimes where people are ascribed illegality or/and incorporated into labour exploitation regimes.[4] Bordering aim less, according to this purview, to stop people than to manage the timing and rhythms of people’s mobility to fit state-capital interests. Although bordering suggests flexible and mobile borders, geographies of border territories remain important, for instance, the carceral spaces of detention centres on islands and border policing in oceans.[5] Yet, border geographies are also performative in a temporal sense: waiting often structures the lives of migrants and causes them to experience a ‘stuckedness’.[6]

As movements of things and people become increasingly intricate, bordering methods tend to dialectically re-invent themselves. Today, the digital – as in the digitalisation of society and the digitisation of information, registers, census, maps, and Big Data etc. – creates an additional and supplementary geography, space, and embodiment for bordering. For instance, when considering the EU digital identity initiative to create interoperable systems for smoother mobility of EU citizens, we need to shift attention to how these practices produces the opposite for those excluded from the right to move freely.

In general, the accumulation of data through the constant growing devices connected to the digital sphere, carries risks of becoming weaponised. The interoperability of different sources of data give rise to new ideologies of predictability and detection of risk. The accumulative practice extracting data from everyone and everything to produce knowledge about certain population deemed as threats, makes us all complicit in the production of digital bordering. Hence, borders do not only cross the lives of migrants or refugees, but they separate, categorise, and discriminate all of us in invisible yet, by the global majority, violently felt ways. The gathering of data and the interoperability of data sets, produces discriminatory correlations, often reinforcing inequalities and overdetermining borders. The roots of these analytical correlations made thanks to Big Data, which are used to manipulate population behaviour, Wendy Hui Kyong Chun argues, can be found in statistical innovation by early 20th century biometric eugenicists.[7] Thus, borders, bordering, and digital bordering, builds on previous forms and methods of violence and on colonial and racial regimes.

Avoiding a state centric understanding of borders, Gloria Anzaldúa, provides us with perspectives that bring the ambivalence and the hybridity of borderlands to the fore.[8] People who become the border also have the potential to resist it. Although digitalisation and increasingly sophisticated techniques of surveillance and security serve to police the border, empirical studies illustrate contestations and autonomy of migrants as their lives cannot easily be represented by algorithmic logics.[9]

Cloud infrastructure

The Cloud combines a particular hardware and software approach with subscription as an economic model. The term 'Cloud' is a "a kind of encompassing atmospheric metaphor"[10] which by now has become a commonplace way to refer to centrally managed computational or digital infrastructure. The Cloud is currently the dominant model for delivering compute across a growing number of industries, from financial markets and health institutions to game industries, mining, governments, agriculture and logistics. In recent years, the reliance on this type of infrastructure has significantly expanded with the integration of sophisticated AI into many mundane tasks. The economic model of The Cloud is based on 'pay-per-use', promising to eliminate overprovisioning and adding flexibility for new or unexpected demands. On-demand computation is profitable in the short run because it allows organisations to shift Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) to Operational Expenditure (OPEX), meaning they own less physical assets such as property, buildings, technology, or equipment, and they can therefore increase their cash flow. In the long term, it creates increasing dependencies, costs that fluctuate and depletion of expertise. For delivering services such as file storage and on-line applications, Cloud infrastructure deploys specialised software on multiple interconnected servers to carry out the desired amount of computation. It consolidates an agile approach to software production which allows for continuous, centrally managed updates which in turn necessitate clients to remain always connected.[11] Ultimately, The Cloud exports agility to many areas of life as it shifts the management of and responsibility for core operations away from industry, governments and institutions.

Compute

As a verb, to compute could simply mean using a computer, calculating or making sense. More recently, in the context of Cloud infrastructure, compute is being used as a noun to signify the combination of processing power, memory, networking and storage that is required to run software applications. The objectification of computing (from verb to noun) is synchronous with the rise of IaaS (Infrastructure-as-a-Service), PaaS (Platforms-as-a-Service), SaaS (Software-as-a-Service), and eventually XaaS (Anything-as-a-Service), "the extensive variety of services and applications emerging for users to access on demand over the Internet"[12]. Cloud companies such as AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud provide units of compute that are calculated as time-slice tickets to allocated resources which will be 'served up' by a data center. By assembling hardware, software, and network-architecture into flexible commodities, computing capacity can be sold by the hour or second.

Anna: Add a sentense on what infrastructure-as-a-service is.

Femke: updated!

Crisis

Crisis has become a polymorphous concept – in particular since critical debates transcended an often narrowly interpreted understanding of Marxian concepts of crisis related to economic contradictions and dynamics (e.g. overproduction, underconsumption, tendency of the rate of profit to fall). The concept has been altered from singular to plural as the focus has shifted toward multiple crises or poly-crises of capitalist social formations or global capitalism. Nevertheless, some categorical considerations can be highlighted. In an early debate on social and political crises (in Late Capitalism aka Fordism) Jürgen Habermas stated:“crises arise when the structure of a social system allows fewer possibilities for problem solving than are necessary to the continued existence of the system. In this sense, crises are seen as persistent disturbances of system integration.” (1988/1973, 2) He pointed out that crises emerge from structural contradictions of (capitalist) societies and the growing inability of social institutions (e.g. – but not exclusively – state institutions) to tackle them. However, he also pointed out that there is a “discursive” element to crises as the interpretation of a certain social dynamic as “crisis” has to become widely accepted. Something which nowadays is also labelled crisis construal or crisis narratives by people like Bob Jessop and Ngai Ling Sum. This also means that it is important how crises are socially constructed as this influences the conflicts and struggles about new forms of crisis management and/or social transformation.

The shift to concepts such as multiple or poly-crises aims at a non-reductionist interpretation, where crisis is not only determined by the dynamics and contradictions of capital relations. Instead, such conceptualisations refer to the relative autonomy of social contradictions and crisis tendencies in different social spheres (state, care/social reproduction, environment etc). The challenge is to grasp their interdependencies and the way they are mutually overdetermined and maybe reinforcing each other. There are also contributions which highlight the significance and connections of crisis developments in certain social spheres such as the economy or the environment. To give an example, Klaus Dörre is talking about a “Zangenkrise” (pincer crisis), generated by the mutually reinforcing developments of global warming and the capitalist “Landnahme” (seizure/land grab) of more and more social spheres.

Societies in which the capitalist mode of production is dominant rest on certain strategies to externalize its socially dysfunctional and useless, and as a consequence maybe even destructive effects to other (social) spheres (individuals, society, nature). Historically, extensive social struggles had to force the dominant social forces in capitalist social formations to stabilize the crisis inducing consequences of the subsumption of societies to capitalist social relations through the imposition of welfare systems. This helped to stabilize the destructive effects of the dynamics of accumulation processes on societies and their reproduction while securing the reproduction of the relations of power and dominance.

The evolving planetary crisis brought about by climate heating is another effect of the externalization of the destructive and dysfunctional effects of the capitalist economy based on profit seeking, competition and permanent growth. Societies in which the capitalist mode of production is dominant use the environment as ecological sink for its emissions, waste etc. Even though the ecological crises are unfolding according to their own, still not fully predictable logics they have become a contested field as their effects are retroactively affecting the very reproduction of societies as well as the capitalist economy. The unfolding struggles are about the question whether the ecological crises demand a fundamental reorganization of the economy or whether they can be tackled through the very logics causing them in the first place. The discourses about technology-open solutions to the ecological crises aim at relying on the alleged capacity of capitalism to constantly revolutionize the forces of production. They ignore the fact that in capitalist economies this is only an option when it generates profits. Debates about the “Twin Transition“ which aim at combining the ecological transformation of capitalist economies with far-reaching processes of digitalization and technological transformation point to extensive search processes to not only secure the expanded reproduction societies in which the capitalist mode of production is dominant but also to tackle the multiple crises that are affecting it.

In the debates about the shift from Fordism (resting not only on a certain regime of accumulation and regulation but also on a specific technological paradigm) to “post-Fordism”, whose shape is still contested, an important distinction has been made concerning the scope and depth of structural or major crisis. The developments since the 1970s/80s were interpreted as a period of fundamental (multiple) crises, affecting more or less all spheres of society. As outdated forms of crisis management failed to solve these crises, farreaching structural social transformations were sparked. In mainstream social science (for example in Neo-Schumpeterian debates but also in some Marxist traditions) technological changes and disruption through “radical innovations” or the revolution of the productive forces are on the one hand understood as a crucial driver of crisis, undermining the historically specific and therefore temporary regulations, embeddings, social and spatial fixes (or whatever concept might be used) on which capitalist social formations rest. The ability of those fixes and regulations to stabilise the contradictions of societies in which the capitalist mode of production is dominant, is therefore eroded. On the other hand, these approaches tend to present technological developments and transformations as rational and undisputable solutions and strategies of crisis management to secure a new period of growth or the expanded reproduction of capitalist social formations.

Thus, it has to be highlighted that technological transformations, the emergence of new technological paradigms (e.g. digitalization) are closely connected to social struggles and conflicts concerning their shape and trajectories. They cannot be separated from the power relations in actual capitalist social formations. Furthermore they are able to affect and permeate all social spheres and social interactions. The contested character of technological transformations also allows us to understand why the agents (“Träger”, Karl Marx) of these processes can act as disruptors in certain social conjunctures (e.g. the ascending tech-oligarchy and its alliance with emerging far right and neo-fascist government projects) using technology as an instrument to bring about crisis and transform societies through it.

Mauricio: This is a rich and informative post about "crisis". I like it a lot! One thing that I thought about is that it could perhaps be related to digital transformation a bit more. It is there in the last paragraph, but I think this deserves perhaps one or two more sentences. Also, in relation to “poly-crises”, perhaps it is possible to weave in the planetary crises that the twin transition supposedly solves energy crisis, food supply crisis, democracy crisis, inequality, environment crisis, dependency etc. This could perhaps fit in towards the end of the second paragraph. However, I very much like this entry’s style and focus and wouldn’t want to change much.

Kim: I agree with Mauricio, this is a very rich and informative text. Some sentences were a little bit convoluted; I’ve tried to straighten them out and clarify them here, without changing anything of the significance.

Twin transition

In response to climate change urgencies, governments are combining increased digitisation efforts with plans for a greener future.[13] For example The EU[14], Switzerland[15] and the UK[16] have issued policy frameworks promoting the "twin digital and green transition" as part of their commitment to Net-Zero. The idea of the twin transition as the road to a new regime of accumulation is especially pronounced in the European Union's Green New Deal, which stresses the necessity "to leverage the potential of the digital transformation" and raises the prospect of a "sustainable model of inclusive growth" on the basis of a circular economy.[17]

To achieve this goal, various technological fixes for a range of problems within the process of production and social reproduction are put forward. Investments are made in for example blockchain technologies and cryptocurrencies because they "could be used in material tracing, promising to aid the circular economy by better maintenance and recycling”.[18] 'Digital Twins', virtual models based on large amounts of captured data, "can model, among others, traffic, to optimize traffic flows, reduce jams and slash emissions in the process.”[19] By adding a digital layer on top of common infrastructures such as mobility, energy, healthcare and education, the twin transition claims to make these infrastructures configurable and more easy to monitor. All in all, the role of digital technology in these imaginaries is to ensure the avoidance of waste and an increase in efficiency and transparency, which is associated with an increase in sustainability. What is often left out of such propositions is how the twin transition is itself resource intensive, as it relies heavily on so-called Artificial Intelligence for deciding what is efficient. It increases the need for computation, and therefore additional data centers need to be built which consume electricity, clean water, arable land and metals. The reliance on digital technologies for basic public infrastructures might also create issues with privacy and security, and reshape governance structures as dependencies on Big Tech players increase and decision making processes are informed by algorithms. Furthermore, the promise of green growth within a circular economy on the basis of digital infrastructures rests on the denial of decades of research that has clearly shown that the decoupling of economic growth from environmental devastation is impossible and at the current conjuncture represents a dangerous illusion.[20] The promise of the twin transition is to offer the prospect of a green reorganisation of society without having to question the capitalist growth imperative in any meaningful way. With the discursive fusion of digital technologies and the ecological shift, the prospect of a circular economy that is efficient, profitable and sustainable becomes the only reasonable response imaginable to climate change.

Anna (4/7): Thanks for working on it! I like it a lot and all the important points that came to my mind are included. Also resonates with our interviews.

Anna: Could think of making a keyword on Twin Transition and then having this text. I like it.

Femke reworked as Twin transition

Digital Infrastructure

Digital infrastructure interconnects both physical and virtual technologies to deliver computational processing power, digital file storage and software applications to billions of devices. While the term lacks a precise definition, it is used by policy makers to gesture at an infrastructure-of-infrastructures which includes The Internet, but also mobile telecommunication networks, satellites, sensor networks and Cloud computing. Digital infrastructure is sometimes referred to as "computational infrastructure" because it involves large amounts of computing hardware, distributed over strategically located data centres that are connected through public and private networks. It is dependent on particular software architectures, such as virtualization and Advanced Programming Interfaces (API’s), as well as undersea cables, computer chips, mobile devices, Internet browsers, 5g masts, lithium batteries amongst others. Operating across diverse geopolitical and financial contexts, digital infrastructure is rapidly evolving, requires continuous updates and consumes an increasing volume of exhaustible resources such as clean water for cooling, critical metals and electricity. Despite ongoing investments by nation-states and the EU, the biggest part of digital infrastructure today is managed by global Big Tech companies such as Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft. These companies are owned by shareholders, who need to prove growth year on year. Their services therefore move into new areas continuously, increasing the need for more digital services, or more compute. Whether it is to shift packages across the globe, organizing for resistance against apartheid, or executing border policies, digital infrastructure has become a condition for existence, with no more outside.

- on the last sentence: i think it is correct to say that digital infrastructure is a apriori condition for existence, but i feel that the "no more outside" could be framed as a question or rather, as a call to further think through immanent modes of critique that are not necessarily based ony any kind of "outside". Berlin-SoLiXG (talk) 15:00, 7 February 2024 (UTC)

Notes 26.1.2024

- great, maybe re-iterate the maintenance and continuous work on the infrastructure? - stress the elacticity of the term? Stress that there is little definitory work on the term available? - Helen's suggestion: "Cloud infrastructure is currently dependently dependent on both APIs, storage, as well as cables, data servers, computing processers, undersea cables, sensors, mobile devices, apps, browsers, precious minerals and batteries amongst others!"

Digital Non-Sovereignty

A conversation is missing on the brokenness of our infrastructural imaginaries. This entry describes an imaginary concept which, in contrast to it’s antonym Digital Sovereignty, is unlikely to be found in policy papers, political analyses or European decrees. No results found. Digital Non-Sovereignty is an invitation to approach[21] the digital sphere from and with it’s economic relations, interconnected networks, dependencies on resources and supply chains. Easier said than done, this means to take into account how digital infrastructures are implicated in continuing violent acts of colonialism. Generation Lumière, an international solidarity movement that campaigns for the diasporas to have the power to resist ecocide, states the obvious: “Digital technology is not just a ‘virtual’ world. Through its infrastructure, it generates other realities that are very concrete. The first of these realities is its growing need for minerals, the extraction and production of which have disastrous environmental and societal consequences.”[22] How to stay with the concrete realities that interconnect the lives of collectives and individuals, lands and bodies, the phone that is warming your pocket and the disastrous extraction of cobalt in the Republic of the Congo? It is here that “non-sovereignty”, a concept proposed by queer theory scholar Lauren Berlant, might offer a way to approach the vulnerability which results from everything being in open relation to each other. As they write, “What emerges are other ways to process inconvenience, the evidence that you were never sovereign — evidence the world forces you to face and a fact about which much genuine and confusing ambivalence ensues.”[23] Brought into the digital sphere, the concept of non-sovereignty provokes an infrastructural imaginary that refuses to bring the interrelations to other lives and lands in as an afterthought, an inconvenience in the way of obtaining Digital Sovereignty. Importantly, Digital Non-Sovereignty differs from the convenient arranging of interstate relations that is gestured at in “Strategic Autonomy”. In the context of Brexit and cooling relations between Europe and the US, Strategic Autonomy had an upsurge and pointed at the aspiration of the European Union to “promote peace and security within and beyond its borders.” The concept does some thinking through dependencies, but it’s end-game is finding the optimal trade-off between security and openness in a struggle for control among violent battles for global hegemony.[24] In the words of Nathalie Tocci, architect of A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign And Security Policy in which the concept prominently figures, “The two sides of the same coin are protection and promotion”[25] — Strategic Autonomy as just another gesture of Fortress Europe. Why is it unimaginable to address historical harms first, before jumping into the creation of yet other ones? Rather than shifting billions into the scaffolding of aspirational AI infrastructures in an attempt to attain Digital Sovereignty, Digital Non-Sovereignty would mean instead to begin with the damage already done, to care for the implications of ever expanding digitization from the start. Here we start to see the limits of Digital non-sovereignty as a concept that could help us to divest from the all-consuming mirage of Digital Sovereignty; it’s antagonistic orientation might distract us from the urgent work to also hold on to, in the words of Berlant, “attachments, motives, and interests from within the lived space of an ongoingness that we want both to shred and maintain something of.”[26] To continue a conversation on the brokenness of our infrastructural imaginations, a next entry might need to think with Digital So-and-sovereignty for example[27]. This purposefully ambiguous concept invites a non-binary approach to past, present and future infrastructurings, a necessary ambivalence for figuring out how to move away from the reactionary accelerationism which replicates and expands a harmful extractive economic model that is increasing the unjust distribution of wealth, devastating the planet and actively undoing institutions, welfare, and governance in the process.

Mauricio: This was refreshing to read! I enjoyed it a lot. I think however that there are some formulations that could be a bit clearer. This sentence for instance: “Digital Non-Sovereignty is an invitation to approach the digital sphere from and with it’s economic relations, interconnected networks, dependencies on resources and supply chains, but also from and with the historical responsibility for violent acts of colonialism”. Important as this sentence is, I think that it would be easier to follow if it was broken up; the use of “from” and “with” becomes a bit confusing.

Also, I think that it works well as a keyword. We have some that are explanatory, and then a couple, like this one and, I think, the crowd, that are a bit more playful and experimental, twisting concept in policy to create something else.

(Digital) Sovereignty

The most simple definition of sovereignty is that it denotes the exclusive power of an authority within a given territory, represented by the state. Wendy Brown has furthermore argued that sovereignty ideal-typically consists of six features: 1) Supremacy: there is no higher authority than the ruling body. 2) Perpetuity: there is no term limit for authority. 3) Decisionism: the ruling body is not bound to law. 4) Absoluteness and completeness: Sovereign power cannot be probable or partial. 5) Nontransferability: the sovereign power cannot be conferred without canceling itself. And 6) Territoriality: the sovereign power is delineated to a specified jurisdiction, a territory.[28]

The concept of sovereignty was first coined during the epochal changes within Europe in the 16th century. Maybe not its first but certainly its most famous iteration was developed by Jean Bodin in his Six Books of the Republic (1576). The background of Bodins intervention was the conflict between central monarchies and feudal aristocracies connected to the advent of absolutist states in Europe. The epoch of Feudalism was described by Perry Anderson as an era of „parcellized sovereignties“.[29] Absolutist regimes concentrated political and military power in the hands of one single governmental entity personified by the absolute monarch. But they were never completely successful in replacing feudal power structures. It was only through the combined process of the development of capitalism, colonialism, bourgeois revolutions and nation building that a modern form of sovereign statehood actually superseded the feudal order.

Modern sovereignty on the other hand is not only connected to the sovereign state, but also to the notion of popular sovereignty. State sovereignty, as Balibar has argued, is founded on a contradictory balance whereby popular sovereignty is at the same time enabled and circumscribed by the polity.[30] The concept of sovereignty has therefore a dual and conflictual character: It refers at the same time to the protection of individual rights from and popular participation in the state, while at the same time protecting the freedom of the state from competing power centers and prescribing obedience to its subjects. Furthermore, the meaning of sovereignty is expansive in its potential. Over the recent decades more and more non-state centered meanings, such as notions of body sovereignty or food sovereignty, have established themselves. At the same time national sovereignty is more and more understood, by forces on the left, right and center, as being hollowed out by globalization and technological changes.

The contemporary debate around „digital sovereignty“ is situated within this contradictory developments and is characterized by the same dual and conflictual understanding of sovereignty mentioned above, referring sometimes to the protection of individual user rights and sometimes - or at the same time - advocating for the revitalization of state sovereignty over the unchartered territory of the digital world. We understand digital sovereignty as a discursive tool within a wider hegemonic project, situated between previous conceptualisations of digital sphere and governance, such as data sovereignty and cyber sovereignty. The term refers both to a nation-state perspective of sovereignty and an individual and rights perspective. In European integration policy context, DS works as a catch-all term entailing the entire value-chain of the digital sphere, from cloud infrastructures to cables and data centres, to the production of minerals and semi-conductors, which entails regulations regarding data surveillance, data extraction and privacy, and strategic geopolitical positioning.

Imagined community

The idea of "imagined communities" famously stems from Benedict Andersons seminal text Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (1983). At its core lies a historical account of the emergence of the "nation" as the paradigmatic form for political self-determination in modernity. According to Anderson, the nation, is an imagined horizontal affiliation that is pictured as bounded - it has limits beyond which lie other nations - and as sovereign - it aspires to rule itself. It arrives into the space created both by the waning of religious communities and their sacral languages, as well as the idea of political rule through divine authority.

Crucially, Anderson stresses the role of media technologies in the emergence, and in the maintenance of nations. The printing press and its commodities - the novel and the newspaper - allow for a shared sense of time and rhythm to develop across geographical distances. When opening the morning newspaper, each reader "...is well aware that the ceremony he performs is being replicated simultaneously by thousands (or millions) of others of whose existence he is confident, yet of whose identity he has not the sligthest notion. (...) Observing exact replicas of his own paper being consumed by his subway, barbershop, or residential neighbours, (the reader) is continually reassured that the imagined world is visibly rooted in everyday life."[31] Beyond the conditions of "print capitalism", however Anderson outlines technologies of state power for the maintenance and management of a nation. The Census, allowing for the quantification and categorization of a population, the Map, delineating the borders of the nation and the territory of its sovereignty, and the Museum, the forging and fixing of a mythological past detached from the present.[32]

In line with other authors such as Michel Foucault[33] or James C. Scott[34], he consideres how states draw on technology in order to govern and manage subjects. Anderson does not offer a general theory on the construction of social groups, but a historical account of the emergence and maintenance of one specific form. His work inspires our inquiry into how political and social affiliations and boundaries are created under specific historical and technological conditions.

Resilience

Resilience is generally understood as the capacity to quickly adapt to or recover from shocks. It was coined in the 19th century after the Latin word resiliens (rebounding or recoiling) and was meant to describe the trait of certain materials to return to its initial shape after being impacted by exterior forces. Nevertheless, it was only in the latter half of the 20th century that researches in the fields of psychology and ecology developed the word into a scientific concept. In this context it was adapted to not only delineate the capability of ‘bouncing back’, but to ‘bounce forward’, i.e. to recover and improve at the same time. The ecologist Crawford S. Holling was especially important in developing and popularizing the concept. In an influential article from 1973 he criticized the then hegemonic understanding of ecological systems as governed by equilibrium states and theorized them instead as systems that have to continually adapt to unforeseen disruptions and sudden changes. [1] As a philosophical position resilience-thinking entails four central pillars: (1) the assumption of an ontology of volatility, i.e. a “random world” [2] that is in constant instability, disrupted by indetectable forces from without and within. This also translates in a conception of social agents as being in a constant state of vulnerability, since actors are permanently exposed to dangers due to abrupt changes in their environment. Derived from this resilience-thinking postulates (2) an epistemological defeatism, i.e. a view of disruptions and crises as unpredictable and at the same time inevitable events. David Chandler has described this onto-epistemological commitment as one that sees the world as consisting of “unknown-unknowns” [3] by which causal mechanisms underlying events can only be known post-hoc. From this follows (3) a cataclysmic optimism which makes a virtue out of necessity and frames disruptions, shocks, crises and catastrophes not as negative eventualities one should try to avoid, but as chances to adapt, to learn und to improve. The resilient subject is thus constructed as one characterized by spontaneous adaptive rather than reflexive agency, viewing existential uncertainty as an opportunity rather than a burden. Translated into governance, resilience thinking therefore privileges (4) micro-strategies of adaption to unforeseeable events, centered on small units like communities over large-scale crisis prevention, that seek to avoid disruptions and try to maintain stability and equilibrium for society as a whole. As a mode of governmentality, resilience was shaped in the early 2000s in reaction to sudden shocks to Western societies such as different crises. The European Union defined it in 2016 as “the ability of states and societies to reform, thus withstanding and recovering from internal and external crisis”. [4] The notion of resilience is a concept of particular interest in the current era of disruptions, which has been termed a 'polycrisis'. This is due to its function as a guiding concept in times of crisis. Economic, ecological, medical, political and social crises and catastrophes are increasingly seen as a constant feature of society. They are understood to be at the same time more probable and also as inherently unpredictable. While the concept of resilience has historically been associated with neoliberal governance frameworks, recent applications have emerged in the context of geopolitical dynamics, advocating for a state interventionist approach. This shift has placed significant emphasis on issues pertaining to digital technologies and infrastructures, underscoring the integration of technological and social dimensions in contemporary geopolitical analysis. In this spirit, within the more recent policy discourse of the European Union resilience is bound up with other social imaginaries such as digital sovereignty and the twin transition. Some argue this expansion of the concept have reduced it to a buzzword. [5] Nevertheless, the fact that the imaginary is contested and it is still up for debate, as we can identify simultanities and contradictions in its definition.

[1] Holling, C S. 1973. „Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems“. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4(1): p. 1–23.

[2] Ibid. p. 13.

[3] Chandler, David. 2014. Beyond Neoliberalism: Resilience, the new art of governing complexity. In: International Policies, Practices and Discourses 2(1), p. 51

[4] European External Action Service. 2016. Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe : A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy. LU: Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2871/9875 (28. August 2024). p. 23.

[5] Joseph, Jonathan/Juncos, Ana E. 2024. Conceptual politics and resilience-at-work in the European Union. In: Review of International Studies, 50(2), p. 385

Stack

What’s a stack? Colloquially, the terms denotes a vertical pile of self-same objects. A stack is neat, tidy and stable. A “Stack“ is also a model to conceptualize digital infrastructures as consisting of multiple technological layers, stacked on top of each other. Political and technological sovereignty is increasingly imagined in the same fashion: India’s attempts to create a unified software infrastructure for digital services terms itself the “India Stack”. European policy advisors have recently called for building a „EuroStack”. A model akin to a layer cake guides the distribution of EU funding and regulation into technology sectors, all with the goal to reduce technological dependencies, enhance autonomy and encourage innovation (Bria et al., 2025)

The layered model of digital infrastructure results from the attempts to standardize the diverse landscape of networking practices that existed before the 1980s. Today’s “Internet” was predated by multiple, parallel existing digital networks, including the US-American ARPANET, the French CYCLADES network or the British NPL network, as well as networks of various private companies. The “Open Systems Model” (OSI-Model) as well as the “Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol” (TCP/IP Model) attempted to create blueprints and guidelines that developers and regulators of digital networks could draw on (Russel 2013). Both figured digital networks as stacked layers of infrastructure, suggesting a movement through increasing levels of abstraction: lower layers organize the transmission of physical signals, such as photons through fiber optic cables. Above them lie layers that organize the distribution of data packets to their designated addressees and optimize their routes, reassemble the data packets into their intended sequence, and, at the very top, manage the interaction with user applications such as email clients or messaging services. This model allowed, among other things, to split up and modularize networking practices into differentiated sections, as well as construct relations of dependency between them.

The actual term “stack” for network infrastructures becomes popular throughout the 80s and 90s, increasingly also losing its specificity: In current industry jargon, for example, a “full-stack developer” connotes somebody who can program both on the users’ front-end, as well as on the back-end, pointing towards servers and databases – disregarding “lower levels” of signal transmission or packet distribution (Amazon). The term is picked up in media and political theory, where it attempts to capture the new, disruptive role of technological infrastructure in shaping current political power – sometimes with a totalizing tendency to speak of a singular stack as planetary superstructure (Bratton, critically Lovink and Rossiter). In the context of the geopoliticization of digital infrastructure, the idea of a stack is increasingly popular with policy experts. The resulting models bear little resemblance to the technical specificities of the OSI or the TCP/IP stacks. The layers of the India Stack include the “contactless layer” or the “cashless layer”. The EuroStack’s lower layers include “Raw Materials” and “Chips”, the upper crust is “data and artificial intelligence”.

Digital Networks are not as orderly as the stack suggests. Networks are messy, in the sense that their sometimes-haphazard construction violates the neat ideas of standardization attempts. Actual networking practices do not abide by the borders and dependencies outlined in models. Some protocols violate layers, cut across or tunnel through them. Networks are also messy in the sense that they are dirtied by the non-technical stuff of soil, of human labor, of society and of history. The idea of the stack itself is a discursive object hailing from the field of computer science (Solomon 2013). It serves to paint networks as isolated from ongoing human activity, maintenance, development and political contestation.

Concepts such as the India Stack, EuroStack or the China Stack could indicate two things: that “stacks” indeed provide a model in which (supra)national delineations and power are currently conceptualized and potentially reconfigured. Or, that the jargon of technologists has become so pervasive in the political rhetoric of the current moment, that it is simply the latest tool for lending protectionist geopolitics an innovative sound.

Barros, Bryce, Nathan Kohlenberg, und Etienne Soula. 2022. China and the Digital Information Stack in the Global South. Washington, DC: The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund.

Bria, Francesca, Paul Timmers, und Fausto Gernone. 2025. „EuroStack – A European Alternative for Digital Sovereignty“. 127 p. doi: 10.11586/2025006.

Lovink, Geert. 2019. Sad By Design. On Platform Nihilism. London, UK: Pluto Press.

Lovink, Geert. 2020. „Principles of Stacktivism“. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society 18(2):716–24. doi: 10.31269/triplec.v18i2.1231.

Rossiter, Ned. 2019. „Uneven Distribution: An Interview with Ned Rossiter“. Public Seminar. Abgerufen 11. Oktober 2024 (https://publicseminar.org/2019/05/uneven-distribution-an-interview-with-ned-rossiter/).

Russell, A. L. 2006. „‚Rough Consensus and Running Code‘ and the Internet-OSI Standards War“. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 28(3):48–61. doi: 10.1109/MAHC.2006.42. Solomon, Rory. 2013. „Last in, First out. Network Archaeology of/as the Stack“. Amodern 2.

(these comments resulted from a discussion between Anna and Femke)

- Should the keyword be 'The Stack' or 'Stack' (or even 'Stacking', ref. Geert Lovink)?

- Describe the stack as an imaginary? It seems that is what you are doing, but would be good to make it more explicit! F.e. would help to understand the last sentence for the techno-essentialism it entails: "the jargon of technologists has become so pervasive in the political rhetoric of the current moment, that it is simply the latest tool for lending protectionist geopolitics an innovative sound."

- It seems important to connect the imaginary of the stack to Digital Sovereignty (also to make relation to project more explicit)

- 3rd paragraph, 'losing its specificity' -- if we locate stacks into programming practice (push and pop), it already has transformed when coming to denote infrastructural layers.

- "disregarding “lower levels” of signal transmission or packet distribution (Amazon)." -> not understandable for everyone probably, what does Amazon mean here (they distribute packages too :-))? What is a packet distribution?

- Side note: What does the use of the binary of 'messy' vs 'clean' do, and what that does for understanding the imaginary of the stack. Insisting on the contrast between 'dirty' and 'clean' is maybe not so helpful for addressing the urgent need to consider the impact of digital infrastructure for human labor, environmental destruction, historical debt into account when attempting to imagine infrastructures otherwise.

Technological Solutionism

In light of the multiple crises of contemporary capitalism such as the climate crisis or the crisis of social reproduction, once again technology is often seen as a panacea. While the technological determinist sentiment that technologies could solve societal problems has been around for much longer, Evgeny Morozov’s (2013) concept of technological solutionism has been gaining a lot of traction since coining it. Understood as a whole ideology around the ‘technological fix’ [1], Morozov conceptualizes it as

„[r]ecasting all complex social situations either as neatly defined problems with definite, computable solutions or transparent and self-evident process that can be easily optimized – if only the right algorithms are in place!“ [2]

In SoLiXG we critically reflect the ideology and imaginary of technological solutionism, since framing all problems as merely technical is drastically narrowing down the scope for action within the far-reaching crises and thereby also limiting political intervention and contestation. Additionally, technosolutionist crisis-solving is not an end in itself, it is much more a a way for capital to render “the world’s biggest problems [into] … the world’s biggest business opportunity” [3].

Early criticism of this ideology, which is connected to progress and modernity stems from feminist scholars [4] who raise questions such as whether “science and technology are the solution to world problems, such as environmental degradation, unemployment and war, or the cause of them” [5].

The concept of the Twin Transition contains a technological solutionist logic, when digital technologies are imagined to mitigate the climate crisis and support a green transition. While the available technologies have changed, the idea itself is not new. The nuclear scientist, self-proclaimed technological fixer and king of the technological optimists Alvin Weinberg, for instance, highlighted nuclear energy as a solution to air pollution [6] [7].

[1] Maibaum, A., Bischof, A., Hergesell, J. (2023). Wie kommt die KI in die Pflege – oder umgekehrt? Drei Probleme bei der Technikgenese von Pflegetechnologien und ein Gegenvorschlag. In: Pflege & Gesellschaft 28(1), 7-22, p. 8

[2] Morozov, E. (2013). To save everything, click here. The folly of technological solutionism. Public Affairs /Perseus Books, p. 5

[3] Nachtwey, O. & Seidl, T. (2024). The Solutionist Ethic and the Spirit of Digital Capitalism. In: Theory, Culture & Society 41(2),91-112, p. 92

[4] Aulenbacher, B. (2005). Rationalisierung und Geschlecht in soziologischen Gegenwartsanalysen. Springer Verlag.

[5] Wajcman, J. (1991). Feminism confronts technology. Polity Press, p. 1.

[6] Rosner, L. (Ed.). The Technological Fix: How People Use Technology To Create and Solve Problems. Routledge.

[7] Nye, D. E. (2014). The United States and Alternative Energies since 1980: Technological Fix or Regime Change? Theory, Culture & Society, 31(5), 103–125.

FS: Glad to have this keyword, and to see it so clearly connected to the project. It is quite short, and I wonder if you could say something more about the way that techno-solutionism operates with twin transitions, making problems and solutions but also making a world. The citations you included hint to this, but I would love to read a bit more about how this is not just about greenwashing compute while electricity and water use, mineral extraction etc. sky-rocket. It also about how tech-companies are actively intervening in the world to restructure it according to their own image. We have been reporting on this in the case of Frontier, where both a market and a digital infrastructure are created to provide a so-called solution that will continue to expand the desire for more compute.

The crowd

Since the beginning of industrialization and dawn of democracy the crowd has been the great unknown, the indeterminable variable of history. Not quite a political constituency (demos), nor yet fully an ethnic community (ethnos), the crowd is made up by those who fall through the cracks of economic, political, epistemological, and ideological systems of representation, only to make such systems crack up as soon as they emerge from the social depths and present themselves as a force of historical change. A “phantom public” (Lippman), “the non-existent” (Badiou), an “unidentifiable social object” (Fassin), the “silent majorities” (Baudrillard): the crowd attains such epithets from its position beyond the threshold of sociological intelligibility. As Adorno put it: “the crowds [die Massen] are always the others”.

Since the invention of photography, each new media technology has been hailed as an instrument able to bring the mysterious being and agency of the crowd into the field of representation, as a tool for penetrating the crowd’s depths, exposing its being, deciphering its modes of existence, indexing its locations, surveilling its appearances, predicting its movements, managing its internal diversity, and exploiting its activity. Interactive digital technology appears in this chain as the ultimate crowd technology, promising to comprehensively register and represent human life within one system, thereby also offering the possibility to monitor, model, and mold human behavior so as to fit desired norms. In its post-digital incarnations, as the posited substratum of crowd funding, crowd sourcing, crowd management, crowd simulation, and impact crowd technology, the crowd may appear docile and obedient, conforming to algorithmically established models – a set of atomized human units responding to selected stimuli, calculated to produce predefined economic or affective values. The meaning of the concept of the crowd is apparently now inverted: no longer a collective whose agency is unknown, the crowd merges with its digital imprint and becomes one with its representation. The crowd replicates itself in the form of the Cloud, which absorbs the features of the crowd within itself. Henceforth, the cloud offers the digitized technical infrastructure of the crowd.

However, like the crowd, a cloud can be represented only from the outside and from a distance (Weizman). Its contours set it off against the surrounding environment, or the blue sky. But once you are inside a cloud, or become part of a crowd, you no longer see them, can no longer represent them. They are similar to a network of relations, an energy field, or a fog: detectable only through whatever expressions, actions, or symptoms they project and present. Hypothetically, therefore, the twinned phenomena of crowd and cloud hold the secrets of the Social Life of XG.

The Social Life

By social life we refer to relationships that exists between individuals and move through individuals. Ceaselessly interiorised and exteriorised, these relationships are mediated by technological and semiotic systems that condition cognition, senses, and emotion. In our period, social life is increasingly mediated and formatted by digital media and platforms. In this project, social life is understood as the surface of interactions, connections, frictions, contestations, continuities, and negotiations that emerge from and in every level of digital infrastructure. The Open System Interconnection-model (OSI), a conceptual framework designed by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO), divides telecommunication technology into seven or eight layers. The first seven are the physical layer, the data link layer, the network layer, transport layer, the session layer, the presentation layer, and the application layer.

These layers describe the technical aspects of transmitting sine waves, access to radio frequency, construction of wires, cables, and data centres, routing and directing data, and user applications such as Facebook or TikTok. All these technological layers are permeated by the social. For instance, the technical transmission of sine waves depends on the radiofrequency they are transmitted. In turn, the state auctions off spectrum to the highest biding operator. The distribution of spectrum is territorially bound but negotiated between nations and industries that are members in ITU. Another social surface concerns the geopolitics of ownership and location of data centres, fibre-optic cables, and cell phone towers. A third example of how the social permeates the technical is the production of data and the value extracted from the seventh layer, the application layer. Expert in the field speak of an eight layer, which is not a technical layer but an acknowledgement of the social. It refers to the legal and political aspects of layer seven – the consumer application – and user rights, but also regulations regarding integrity versus the law of intercept, which gives state agencies the authority to access and decode traffic.

Hence, while the social life of XG recognizes the social implications of rapidly increasing digitization and digital technologies, such as smart phones and internet of things, it also seeks to bring clarity to the social life that takes place in various shapes along all the layers of digital infrastructure, and to the ways in which this contributes to social transformation in a more general sense.

The Social Life (Reworked)

In its broadest sense, "social life" can refer to the entirety of relationships that exist between humans. These relationships are the product of practices - of repeatedly doing, saying and thinking things - , shaped by cognition, senses and emotions. It includes interactions and connections, frictions and contestations, ruptures and continuities. In our current moment, social practices are thoroughly mediated and formatted by digital media and their underlying infrastructures. A first results is that any investigation of "the social life of XG" asks: How do digital infrastructures shape the practices of social life?

Asking such a question has to acknowledge that digital infrastructures are themselves entwined with social practices, and that technology is inseparable from society. A complex infrastructure, such as the World Wide Web, is not external to, but a product of social processes. It is conceptualized by institutions such as the ITU or the ISO, who picture it as a kind of stack that consists of around seven layers. These range from the physical layer of cables and antennas, to the transport layer of transmission protocols and data packets, up to the application layer, where users interact with Facebook or TikTok.

Some experts half-jokingly talk about a "Layer 8" when discussing the role of society and politics on the internet architecture. They mainly refer to regulations of user rights, but also regarding the authority of states to access and decode traffic. But rather than just another layer in some imagined stack, social practices suffuse *all* levels of digital infrastructure. Radio spectrum, enabling the physical transmission of radio signals necessary for global communication, is imagined as a resources that states make available for competition between network operators, and whose distribution is territorially negotiated between nations and industries. The ownership and location of submarine cables, cell phone towers and data centres has become a topic of geopolitical interest. The protocols that determine packet transmission are the result of negotiations at standardization institutions and a topic of conflicts for definitional power.

Hence, while the social life of XG recognizes the social implications of rapidly increasing digitization and digital technologies, such as smart phones and internet of things, it also seeks to bring clarity to the social life that takes place in various shapes along all the layers of digital infrastructure, and to the ways in which this contributes to social transformation in a more general sense.

The State

The state and state power are notoriously difficult to define. Within the social sciences, definitions vary radically in relation to disciplinary belonging, theoretical outlook, and historical scope. Should the state apparatus be emphasized, with its complex ensemble of institutions and organizations, which may exert repressive force on the state’s citizens, but also facilitate democratic co-determination, through representative or other arrangements? Should the state’s territorial aspects be prioritized, highlighting questions of the determination and legitimacy of frontiers, of state sovereignty and inside-outside demarcations, and of inter- or supra-state relations and dependencies? Or should the population of the state be seen as its deciding element, foregrounding questions of citizenship and rights, of “general will” and biopolitical governance, of imagined communities and the nature of nationhood? [1]

All of the above, answers renowned sociologist and state theorist Bob Jessop, and adds a fourth dimension: the state idea, a discursive and performative construct that confers an imagined unity onto “the state” as a heterogeneous ensemble, and that can itself be an object of competing “state projects”, vying for hegemony. “The core apparatus of the state”, Jessop writes,

“comprises a relatively unified ensemble of socially embedded, socially regularized, and strategically selective institutions and organizations whose socially accepted function is to define and enforce collectively binding decisions on the members of a society in a given territorial area in the name of the common interest or general will of an imagined political community identified with that territory.“ [2]

Jessop’s definition, in other words, emphasizes the polyvalent, polymorphic, relational, and porous nature of the state, as a dynamic complex of forces and institutions. It is a model for understanding the state developed in response to a dominant tendency in modern, political thinking, toward essentializing, reifying, and instrumental conceptions of the state. To this day, much political discourse and strategies, on the left as well as on the right, remains caught in the contradictions generated by such notions.

Within liberal and libertarian traditions, the state has generally been thought as a substantial thing that exerts a limiting force upon freedom, conceived negatively as the complete and abstract absence of dominance. [3] According to various versions of contract theory, from Thomas Hobbes to John Rawls, citizens enter into a mutual agreement about the establishment of the state, to which some freedoms are relinquished and some responsibilities are conferred, in exhange for guarantees of security and stability. [4] Politics should aim to minimize the limiting force of the state – reducing it to a “night watchman”, or even, ultimately, according to anarcho-libertarian theorists, suppressing it altogether – in favor of the possibility for private individuals of pursuing freedom and happiness, through economic relations. [5]

At the same time, as many social theorists and historians have shown, liberal and neoliberal policies have in no way always sought to minimize the state. [6] Instead, they have tended toward functionalizing the state, redefining it and restructuring it as a vehicle for stimulating private enterprise or for “encasing” markets (to use Quinn Slobodian’s term), so as to defend them from the “external” threats of labor organization or redistributive or egalitarian policies. [7] Here, the state is a condition of, not a limit to, a functioning, “free” market economy. Such processes are intensified today, through efforts to integrate the institutional infrastructure of state administrations with techniques of algorithmic governance developed, provided, and controlled by major digital platform corporations. [8]

Within the socialist tradition, in a broad sense of the term, the contradiction is even more blatant. On the one hand, in Marxist theories from the nineteenth century onwards, the modern state has generally been conceived of as an instrument of class domination in the hands of the bourgeoisie. [9] The aim of a socialist politics should therefore, as Marx phrased it in a late text, be “a revolution not against this or that legitimate, constitutional, republican or imperialist form of state power [but] against the state itself”. [10] That revolutionary process could take the form of a violent upheaval or of a more long-term “withering away of the state” (Lenin), in favor of some other mode of social organization, unrecognizable as the state form. [11]

On the other hand, the histories of both “really existing socialism” and of social democratic regimes in the west, have evidently not been histories of the state’s abolishment, however slow. Instead, they have been histories of the development of “strong states”, of highly complex state apparatuses with large administrations and/or sprawling security apparatuses, some of which have functioned better than others – from “golden age” welfare states to eastern bloc bureaucratic colossi. [12] This is a living contradiction: whether it should be anti-state or in favor of a strong state remains an unsettled question in much radical left politics to this day.

In the 1970s, the Greek philosopher and sociologist Nicos Poulantzas developed a “relational” theory of the state, that sought to break with reifying and instrumental conceptions, emerging either from the right or from the left. The state, he argued, should not be understood as a monolithic bloc without internal contradictions, that could exert power as an instrument for or a direct expression of a determined political will. Instead, he held, the state and its instutions should be seen as a “material condensation” of the “relationship of forces” (mainly focusing on forces constituted by the capitalist relations of production) that characterize social relations in society as a whole, at the same time as it maintained a “relative autonomy” from those relations. [13] Poulantzas’ model therefore rejected notions of the state as a closed, self-sufficient, coherent entity, that could be controlled, seized, or overthrown from the outside. Political struggles were instead always already “inscribed in the institutional materiality of the state”, where they maintained different degrees of stability, influence, and reach. [14]

With his polymorphic and dynamic concept of the state, Jessop builds on Poulantzas’ analysis. What he proposes is a “strategic-relational” approach that aims to “capture not just the state apparatus but the exercise and effects of state power as a contingent expression of a changing balance of forces that seek to advance their respective interests inside, through, and against the state system”. [15] At a general level, such political work of “advancing interests”, he means, takes the form of multi-dimensional efforts to establish “state projects” that can command the “state idea” and provide a “substantive internal operational unity” to the state apparatus. [16] In order for such state projects to be effective, he continues, with a reference to Gramsci, they must be connected to wider “hegemonic visions”, that elaborate the nature and the purposes of the state in relation to the complex social order of which it is a part, setting up general guidelines for conducting state policy.

Jessop’ understanding of the state is society centered. This means, it is focused on questions about the historically as well as regionally variegated, constantly contested and dynamically changing relations of the state as an ensemble of institutions to the social relations, contradictions and conflicts that are constitutive for social formations in which the capitalist mode of production is dominant [17]. This means that neither the state, nor society can be understood as independent, self-contained or autopoietic social entities that just happen to co-evolve. Rather, critical theories of the state start with the question which specific characteristics and structurations of social relations (in particular the specific divisions of labour) in modern social formations “demand” the institutionalization of an ensemble of institutions which is ascribed characteristics accepted as statehood. Thus, critical state theories highlight the contradictory, open and conflictive character of social relations (relations of production, gender relations, ethnic/racial struturations etc.) as well as the potentially dysfunctional and destructive effects of the dynamics of modern capitalist social formations. These have to be tackled, regulated, managed etc. through the institutions of the state as they are understood as not being able to fully reproduce themselves on its own. Through this, the ensemble of institutions labelled the state is capable to secure and stabilize the conditions of the expanded reproduction of societies in which the capitalist mode of production is dominant while organizing certain social groups (in particular the ruling classes but also subaltern groups as subaltern groups), their interests, political strategies and so on at the same time. Thus, the state is fundamental to reproduce the dominant relations of power and dominance linked to capitalist and patriarchal as well es racist social relations. This perspective on the contested, contradictory and dynamic evolution of the ensemble of institutions acdepted as the state allows to ask how the transformation of the divisions of labour in the different spheres of modern social formations brought about by processes of digitalization, the datafication of social interactions in the economy, politics, the “private” realms etc. might affect the reorganization of states and the capacities to enforce collectively binding decisions in the name of a hegemonic common will.

What could a radically democratic project, encompassing these different levels of social and political organization, be today, in a “post-digital” condition? The terms of mounting such “state projects” and “hegemonic visions” are of course radically shifted in a situation where the administrative infrastructure of state apparatuses, and “civil society” institutions and social relations, are to an increasing degree integrated with governance techniques and protocols of social interaction fostered by monopolistic digital platform corporations, operating at a global scale. Perhaps, as Cédric Durand has recently suggested, any meaningful “digital sovereignty” – however progressive – would today presuppose the establishment of some sort of “non-aligned digital policies”, creating “an economic space outside the grip of the monopolists in which alternative technologies could be developed”. [17]

Notes

[1] Max Weber’s famous definition of the state as the “human community which (successfully) lays claim to the monopoly of legitimate physical violence within a certain territory” combines elements of all of these three dimensions of the state. Weber, “The Profession and Vocation of Politics”, in Political Writings (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), p. 310f.

[2] Bob Jessop, The State: Past, Present, Future (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016), p. 49.

[3] See Isaiah Berlin, Two Concepts of Liberty: An Inaugural Lecture, Delivered before the University of Oxford on 31 October 1958 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958). For another classical discussion, see Herbert Marcuse, A Study on Authority (London: Verso, 2008).

[4] Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (London: Penguin, 1968); John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971).

[5] See e.g. Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (Oxford: Blackwell, 1974).

[6] This is for example a central point in Michel Foucault’s discussion about ordoliberalism and the emergence of neoliberalism, in The Birth of Biopolitics (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

[7] Quinn Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018).

[8] See e.g. Cédric Durand, How Silicon Valley Unleashed Techno-Feudalism: The Making of the Digital Economy (London: Verso, 2024).

[9] See e.g. Friedrich Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (London: Penguin, 1985 [1884]).

[10] Karl Marx, “First Draft of The Civil War in France” [1871], in Political Writings, vol. 3: The First International and After (London: Verso, 2010), p. 249.

[11] Vladimir Lenin, State and Revolution (London: Penguin, 1992 [1917]).

[12] See e.g. Rudolf Bahro, The Alternative in Eastern Europe (London: New Left Books, 1978).

[13] Nicos Poulantzas, State, Power, Socialism (London: Verso, 1980), p. 127ff.

[14] Ibid., p. 144.

[15] Jessop, The State, p. 54.

[16] Ibid., p. 84.

[17] Karl Marx, “Das Kapital”, Bd.1, Werke 23, Berlin, p. 49.

[18] Cédric Durand, ”Fragile Leviathan?”, https://newleftreview.org/sidecar/posts/fragile-leviathan (last visited 25.02.21). See also Cédric Durand and Razmig Keucheyan, Comment bifurquer: Les principes de la planification écologique (Paris: La Découverte, 2024).

XG

In the evolution of cellular networks, experts distinguish multiple "generations" of technological standards, spanning from 1G, the initial analog networks formulated in the 1980s, to the advent of 5G. These generations are the product of continuous technological developments and complex processes of standard setting, which entail the collaboration of various transnational institutions (such as the International Telecommunication Union or the 3rd Generation Partnership Project). They bring together governmental and industrial stakeholders to negotiate technical consensuses on the global operation of mobile communication [35]. The deployment of new “generations” of cellular telecommunication follows a pattern that is well-established in the development of digital technologies. It promises increasing bandwidth, diminishing latencies and novel applications set to revolutionize the private and business use of technology.

While designations like 4G, 5G or 6G attempt to define bundles of technologies and standards, "XG" is an industry term for anticipatory technological iteration, which we expand to capture the process of development, expansion, and maintenance of digital infrastructures, always directing attention to the next generation. As media scholar Wendy Chun points out, this process is never finished and constantly gestures towards the next update. It is driven by crises, such as security risks, environmental imperatives, geopolitical struggles, or armed conflicts [36]. We acknowledge further that it is also simply capitalist growth that drives the constant regeneration of the network by enacting hopes and promises of a better future through new imaginaries and buzzwords such as “negative latency". But while the expansion of technological capabilities appears inevitable, the infrastructures' subjects – be they consumers or customers, users, or producers – are suspended in a state of constant anticipation, waiting to adapt to the newest release. Such a temporal rhythm exceeds cellular networks. Increasing connectivity and computing power involves expanding the material infrastructures that make "the internet" possible. This includes erecting radio towers and antennas, laying optical fibre cables across continents and the ocean floors, building data centers, semiconductor fabrication plants or "Gigafactories" that produce lithium-ion batteries.

I feel that we could also mention in one sentence, that "XG" as a term already implies a thinking-together of imagination and infrastructure? That would allow us to speak of "XG"-infrastructure or somethingt, that implies a socio-technical mix from the get-got. Berlin-SoLiXG (talk) 14:44, 7 February 2024 (UTC)

Notes from 26.1.24

- should we talk about negative latency? - is XG driven by crises, as Chun points out, or by necessary capitalist growth development - By adding "promises", maybe we can avoid reproducing the BS

- Suggestion by Helen to capture the promisory aspect: "XG" is an industry term for anticipatory technological iteration which we expand to capture the promises process of development, expansion, and maintenance of digital infrastructures, always directing attention to the next generation."

SELECTED

Imaginary

- Imaginary v. 2.0